Have you ever, while swirling your favorite dram, looked at it lovingly and wondered, “to what extent is this stuff contributing to the slow destruction of the planet we live on, and by extension, modern civilization as we know it?”

You wouldn’t be the first to ask that question, but unfortunately, there’s not a huge amount of research on the subject. The most comprehensive study of whiskey’s environmental impact to date is a 2007 working paper on carbon emissions related to alcohol production and consumption produced for the Food Climate Research Network. Unfortunately, that study was limited to the U.K., but we still get some interesting takeaways from it.

Breaking down the greenhouse gas emissions associated with Scotch whisky by stages of production gives us the following: The biggest energy expenditure is associated with the actual distilling process, followed by the farms where grain for whisky is grown. Malting and bottle production each contribute somewhat less.

On the whole, for drinkers in the U.K., scotch is a relatively green alcoholic drink. Between beer, wine, and spirits, beer is associated with the highest greenhouse gas emissions, followed by wine. Spirits, as a whole, make up approximately .1% of all U.K. greenhouse gas emissions, and just 7.12% of all alcohol-related emissions. For whisky, the number is even lower, since that figure includes imported spirits—and in the U.K., Scotch is a local product.

That last point is probably the biggest takeaway: beer is associated with higher emissions largely because of the energy it takes to refrigerate it. Wine, in the U.K., outranks spirits mostly because it’s almost all imported. If you subtract the transportation and refrigeration parts, the three categories are close to equal. For someone on, say, the west coast of the United States, a Napa Valley cabernet is obviously greener than an Islay scotch.

What about bourbon?

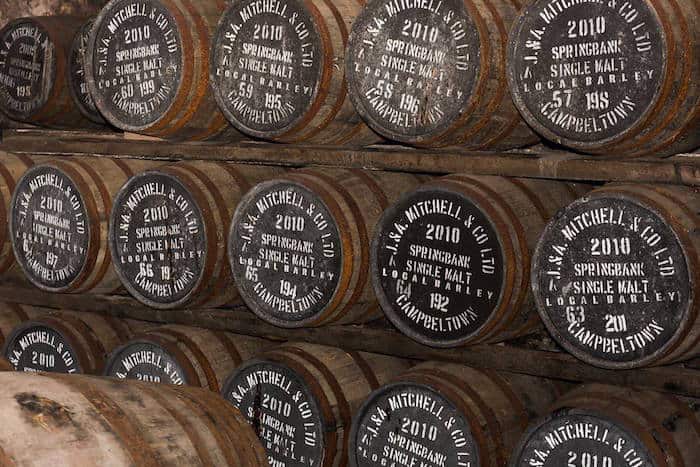

There’s no comparable study for bourbon or other American whiskeys, but we can make some guesses. Obviously, malting is less of a factor for most American whiskeys than it is for Scotch, and if you live in the U.S., domestic whiskeys don’t have to be shipped as far. But we also have to consider that bourbon is aged in new barrels, and those barrels are made of wood. However, according to an article by hardwood forestry expert Tom Kimmerer, the impact of barrel production for whiskey on the white oak supply isn’t huge, and current harvest levels should be sustainable for the foreseeable future.

As far as which whiskeys are greener than others, any whiskey that uses local materials will, of course, have a smaller carbon footprint. Also, column stills are more energy-efficient than pot stills. Maker’s Mark, according to Forbes, “is possibly the most environmentally friendly” alcoholic beverage producer in the world: they use local grain, recycle waste into energy, and have a wastewater treatment facility and a nature preserve on the property that houses their headquarters and distillery.