Editor’s Note: Dick Stoll, a longtime master distiller of American whiskey out of Pennsylvania, passed away late last week at the age of 86. We offer this remembrance as a tribute to him.

I remember the first time I met Dick Stoll. I was invited to join some other Pennsylvania Michter’s fans to sit down with Dick for lunch in Lititz, Pennsylvania, not far from the old distillery in Schaefferstown. I was aware that Dick was 80 years old, so I was expecting, well, an old man.

The man I met was tall and raw-boned with the broad, square shoulders of a lumberjack, and bounced out of his chair to shake my hand like a 30 year old sales rep. He wore new jeans, a creased flannel shirt, and a pair of lug-soled hiking boots.

Honestly, the first impression I formed of Dick Stoll, a hugely experienced distiller, was that this guy, who was 26 years older than me, could likely kick my ass in a fair fight.

I promised myself, and Dick’s friends, that this would be about Dick, not about “I knew Dick,” because honestly, I didn’t know him as well as I’d have liked. That’s the only personal remembrance I’ll make, but it’s a key to knowing the man, because he was not only robust, but he was so personable, so “vibrant,” as Pennsylvania whiskey historian Sam Komlenic put it.

That’s just what Dick was like, and how he made his way. He started work at the distillery in Lebanon County (let’s call it Michter’s, just to avoid confusion; it had other names, but that’s the last and best-known) back in 1955, only a year after Jimmy Russell started at Wild Turkey. Dick started as a laborer, and worked his way up to head of maintenance.

Erik Wolfe, Dick’s partner in the new Stoll & Wolfe distillery in Lititz, asked Dick how he set out to become a distiller. “In typical Dick fashion he laughed and said he never had,” Erik recalls. “Charlie Beam called him into his office. He asked Dick, ‘You work hard, never show up drunk, know every piece of equipment in the place – how’d you like to learn to distill?’ According to Dick, ‘That was that.’”

“Charlie Beam” was what Dick called his boss, master distiller C. Everett Beam, one of the Beams, America’s premier distilling family. That was his distilling pedigree; he learned by working hard for a man who had whiskey-making in his blood.

Dick wasn’t a master distiller, any kind of engineer or chemist or biologist. “He was a practical distiller,” said Komlenic. “He was not formally trained; he learned as an apprentice. He may have been the last practical distiller.” Asking Dick about distilling was like asking Jimmy Russell, or Parker Beam; how things happened, or why, weren’t as important as what happened. They knew every detail of what happened when they made whiskey, and how to make it right.

That’s the main thing to learn about Dick Stoll, to know about him: he absolutely belongs in the company of American whiskey legends like Jimmy and Parker, and Pennsylvania distilling should be immensely proud of him. Here’s why.

Until Chuck Cowdery interviewed Dick in 2009 for his book about the fabled A.H. Hirsch bourbon, The Best Bourbon You’ll Never Taste, Dick Stoll was largely unknown to whiskey drinkers, and even in the industry. If anyone did think about him, they likely thought about the small pot stills that were installed at Michter’s in 1976 (and are operating again at the modern Michter’s Fort Nelson distillery on Main Street in Louisville, Kentucky), and the ceramic jugs of whiskey that you can still find on collector sites.

But Dick Stoll was so much more than that. Just think about this. Dick made whiskey on those little pot stills, but he worked Michter’s column still every day. “The still was gigantic,” says Komlenic. “That was a five-foot diameter still, 70 feet tall! How do I know that? I measured it with a tape measure when I was there in the 2000s.”

That’s a Kentucky-sized column, no doubt, and as the old-timers would say, Dick mashed a lot of bushels. He made Michter’s whiskey (a unique not-quite-bourbon 50% corn mashbill), bourbon, and rye, but he also did a lot of contract distilling. He made rye for Wild Turkey, he made Sam Thompson rye, and he also did a 400 barrel run of bourbon for A.H. Hirsch.

That’s the other half of knowing Dick Stoll: the Hirsch bourbon. In the opinion of people who know bourbon, that batch of bourbon ranks with some of the very best bottles ever made. Cowdery put it in the company of Very Very Old Fitzgerald and the best bottlings of Pappy Van Winkle 23 year old. I have a bottle that Dick signed that I have asked my family to open at my wake.

Dick Stoll made that bourbon, and here’s the secret, the amazing fact that I believe puts Dick Stoll squarely in the company of people like Jimmy, and Parker, and Elmer T. Lee, and Jim Rutledge. That run was, as Dick told Cowdery, “nothing special.” It was the regular bourbon mash, the same yeast, made on the big column still, put in the same barrels. It was about eight days’ production.

The only difference was that the bourbon that Mr. Hirsch contracted went beyond 8 or 10 years in the barrel. It slept in the wood from late 1974 till at least 1989 (there was a small amount bottled at 15 years, most of it a couple years longer). None of Dick’s other bourbon got that chance, we didn’t get the chance, to see just how good it could be. Had we known before, who knows what may have happened?

You know, for years I regretted that Michter’s didn’t quite make it to the bourbon revival that would have seen it, and Dick Stoll, gain the acclaim, the reverence they deserved, something like what has happened with MGP and Greg Metze. Michter’s closed on February 14, 1990. The bank called Dick at the distillery and told him it was over; lock the doors and go home.

He did, and because he was Dick Stoll, and there were no distillery jobs open in 1990, at 57, Dick got a job in construction, pouring concrete. After a while, he found a job in maintenance with a local school district, worked a few years, and then retired.

That might have been that, but for Erik Wolfe, one of a small and dedicated band of enthusiasts who just couldn’t bear the idea of that distillery in the Pennsylvania hills disappearing into history. Wolfe found Dick Stoll, living not far from the site, in Lebanon, and got him talking, as some of us hadk previously. The difference was that Wolfe was determined to make whiskey in that little corner of the world, and he didn’t want to just talk to Dick.

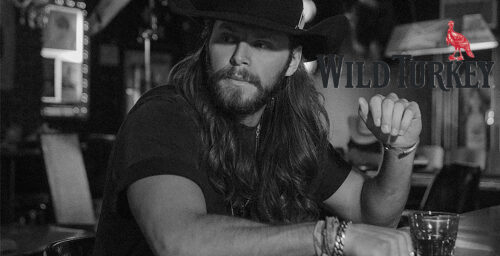

“I set out to learn whiskey making at the feet of a master,” Wolfe says. “I ended up gaining family and wisdom from another generation.” Anyone who saw the two of them – the square-jawed, white-haired distiller and the slender, long-haired distiller-in-training – could tell there was something special about the relationship.

Dick and Eric made their first rye whiskey at Silverback distillery in Virginia, the first whiskey Dick made in 25 years. When the distillery in Lititz came on line, it would be named Stoll & Wolfe, a tribute to the man who’d distilled in the area so many years before.

“While many modern craft distillers thrive on experimentation and exploration,” Wolfe says, “Dick Stoll was a man of tradition. Forty plus years spent honing his craft exposed him to enough unintended variation to know what worked and how time spent in the barrel transformed his contribution to the process.”

That tradition and breadth of experience came home in one of craft distilling’s hottest ideas: heirloom grains. One that is gaining attention lately is Rosen rye, brought back from small amounts of carefully saved grains in seedbanks. Dick Stoll mashed with Rosen rye at Michter’s; he may have been the last person to make whiskey with Rosen rye.

In 2019, he and Erik Wolfe fired up the still at Stoll & Wolfe and did a run of Rosen rye.

Dick Stoll did everything he did almost to the day he died. Komlenic notes that while Dick went to hunting camp for deer season last year “mostly just to be there,” he had also gone in 2018 and got an 8-point buck on the first day of the season. He was 85 at the time.

“Dick was very conscious of his own mortality and knew we’d ultimately lose our race against time,” Wolfe said. “Dick wasn’t one to suffer fools gladly or offer false praise, yet he was the kindest and most giving mentor anyone could hope to have.

“Dick taught me three basic ideals: Be humble, work hard, know your shit,” Wolfe said. “Though he’d never be so bold as to say them out loud or presume to think anyone would care to listen, he walked the walk, knowing it spoke louder than anything he could say.”

The next time you think of the best makers of American whiskey – Jimmy, Parker, Booker, Elmer, Jim, Lincoln, Greg – add another name to the list, a name that’s deserved that recognition for years.