The Glenglassaugh distillery has more lives than a black cat. It’s been mothballed, demolished, and brought back from the dead, quite a few times, but you won’t read much of this “occulted” history on Wikipedia. Yes, some things are better left unsaid…until now.

“Extra, extra, read all about it!” That’s right. You are about to become acquainted with the historical portrait of a distillery that has reanimated itself more times than Herbert West of HP Lovecraft fame.

Glenglassaugh is classified as being a “coastal” distillery, in the Highland region of Scotland. I tend to favor OB whiskies from Glenglassaugh because, as I like to imagine, they’ve been “kissed by selkies,” which have climbed out of the sea to relax in warehouses nearby.

The region is literally brimming with waters of all kinds–from fresh to brackish to salty. As a matter of fact, this (some say haunted) distillery is located in the town of Portsoy, on the north coast of Speyside near Banff and Glen Deveron. Not far yonder, the rivers Spey and Deveron relieve themselves into the North Sea.

Founded in 1875, Glenglassaugh was abandoned, aside from the patronage of homeless squatters (and perhaps selkies) from 1907 to 1931. Operations allegedly revived at this point, and then petered out five years later. However, it’s worth acknowledging that there is some disagreement among Whiskorians (whisky historians) about the “missing five,” as these years have been called.

Yes, some bottles were allegedly found with Glenglassaugh labels, which were said to have been produced from 1931 to 1936, but over the years all of these relics seem to have disappeared. Or perhaps they never existed at all. A few of the oldest Whiskorians assert that the distillery was abandoned in 1908 for reasons that were not strictly monetary in nature. In case you’re starting to drift a little, we are talking about The Supernatural, as in “disembodied spirits that go bump in the dark.” But no matter.

The 1950’s were a time of world-wide rebuilding, and this intrepid spirit of enterprise helped to get Glenglassaugh back on its feet again. New-fangled and larger stills were built, which greatly increased production, and also changed the style of the spirit that was being bottled. However, since fifty-odd years had passed, nobody much remembered how the old stuff smelled or tasted, and so no crocodile tears were shed on this count.

Glenglassaugh went into production around 1960, making a go of it, as they say. Twenty-six years later, all production was halted. Mothballs collected on the floors, and the place once again became home to squatters, and perhaps selkies, the likes of whom may or may not have “cohabited” with human occupants in dankly dark recesses of dereliction.

Glenglassaugh whisky was quite popular with blenders from 1960 until 1986, so very little of the original stock is left. In fact, there’s only ever really been four quasi-official bottlings of Glenglassaugh, with a few independent bottlings that were rare as hen’s teeth. According to the Malt Maniacs website, there were only fifty bottlings left on the face of the earth in 2009. Of these, the “Family Silver” bottling of 1973 (bottled in 1998) is still the rarest and most sought after.

Decades came and went after 1986. The mothballed distillery crumbled into ruin. Yes, it looked as though Glenglassaugh would soon be little more than a giant cairn, until a strange and wonderous thing happened. In 2008, an energy company, named Scaent, bought the hulking remains for five million pounds, and then proceeded to re-animate it into a very respectable modern facility.

Rather than aging the new make, Glenglassaugh decided to release it as “the spirit that dare not speak its name.” This ghostly pale concoction received fairly poor marks among critics. Then again, it couldn’t even legitimately be called a whisky (because of its exceedingly young age). Egad, things weren’t looking so bright for the future of Glenglassaugh. Would the ailing distillery climb out of the red, or would it slide back down the road to ruin, and perhaps even all the way to demolition this time?

The townsfolk of Portsoy weren’t crossing their fingers . . . although more than a few made the sign of the cross as they passed the Old Glenglassaugh Windmill after dark. Rumors still circulated about that landmark. Everyone had a theory about it. The oldest hunchback in town even went so far as to say that the “windmill” was actually a Scottish version of the Tower of Babel, which had been erected by a mad monk in the blasphemous Year of the Toad.

Through the Drinking Glass

Nobody much believed Portsoy’s hunchback septuagenarian, at least about the whole “Year of the Toad” business. Quite a few locals, as a matter of fact, had been raised by God-fearing parents who made it clear to their children, in no uncertain terms, that a monk in the late Middle Ages had begun construction on his “Tour of Babel” in the Year of the Goat.

Later, after the medieval monk’s (alleged) death, his tower was converted into a rather charming and utilitarian windmill. As for the monk, himself, he wondered off into a field after work one evening. Several of his fellow monks reportedly saw their brother lazing amidst the daisies. He sat, and drank whisky, and sang, and drank some more, without ever needing to refill his glass, which he’d taken out from a rather mysterious black silken pouch.

T’was a very odd glass indeed, with a string of topsy-turvy Hebrew letters etched along its brim, all of which seemed to glow through single malt whisky inside, or vice versa. According to rumors, the monk’s song only had six, or seven words, depending upon how the lyrics were interpreted. The tune, itself, was built upon a mystic chord, with bursts of harmonic throat singing, which imbued it with an otherworldly timbre.

At any rate, the lyrics went thus: “Tip Glen Glass, oh tip’er high!” Something odd about the tune, or its words–or rather the visions that both together seemed to induce–caused the other monks to cross themselves, and cover their ears. It was last time the Mad Monk of Babel was set upon by mortal eyes. One minute he was there in the field before them, singing merrily, and the next he was gone.

Some whiskorians contend he was carried up to heaven, while others are quite sure that his song was the last straw, and he was secretly ushered away by the monks, after which time he was either banished from Scotland, or worse. Rufus Loudain, perhaps the most notable whiskorian of all time (long since deceased) had reason to believe that, after the mad monk finished his spirited revelry, the daisies parted to reveal a gleaming black staircase, leading down, down, down . . . into the fiery bowels of hell.

Indeed, the sight of such a wondrous-strange passageway might well have been too much for the monk to resist. Be this as it may, a key, which had been cast from liquid obsidian–at a very high temperature, in some sort of mold–was discovered a few days later by a cow herd. Daisies were still pressed down, and an ominous rectilinear outline was indeed visible in the grass next to the spot where the mad monk had been carrying on. In fact, the grass died and has never grown back in that precise location.

Tourists still visit the spot. A few claimed to have seen the ghost of a man dressed in a monk’s habit, which appeared just after dusk. The events which follow this rare appearance are always the same: The ghost raises his glass of whisky, which gives off a dim light, as though it is some sort of beacon or lantern. He drinks deeply, and sings: “Tip Glen Glass, oh tip’er high!”

Smacking his lips, and rolling his eyes, the taste seems to remind him of something important–at which point, he sets down his glass, drops to his knees, and begins searching through the daisies. Agonizing over what he cannot find, the ghost pounds his fists six times upon the barren sod rectangle. Tears fall from his eyes. He throws up his arms, and then summarily disappears.

For over a century, the medieval monk’s obsidian key was on exhibit at Salty Cod Museum of Portsoy. However, in the late 1990’s, an anonymous patron acquired the obsidian key for an undisclosed sum, upon which time the museum was permanently closed. Many former patrons believe it might currently be in the possession of Prince Philip, who wears it on a chain around his neck for special occasions, although this rumor has never been officially denied or confirmed.

Among the townsfolk of Portsoy, it’s a fairly well accepted conclusion that the Mad Monk of Babel made a three day journey to Satan’s palace of Pandemonium, down a winding obsidian staircase, which opened as a result of his drinking ritual. In fact, to this very day, the mad monk’s song is sung by barkeeps when a particularly ornery patron will not leave after closing time, or when a particularly big and fat patron happens to fall asleep in a booth, and cannot be roused.

Of course, these barkeeps do not know the authentic tune, and most haven’t the slightest idea how to throat sing. Thankfully, no hidden staircases have appeared as a result of their jocular antics. Be this as it may, superstitious patrons always cross themselves, and flee said premises, whenever they hear the familiar old refrain: “Tip Glen Glass, oh tip’er high!”

Resurrected by “Illuminated Ones”

But wait. Our yarn doesn’t end with a talking spirit that has been forbidden to announce its presence, or a haunted old windmill.

At some point, a holding company named Lumiere (French word for “light”) purchased Glenglassaugh, even as a new release was being bottled called “The Spirit that Blushes to Speak its Name.” This time, the new make had been aged for six months in red wine casks, and so took on a ruddy appearance. And so, a company named “Light” took pains to make a transparent just a bit more opaque, and, perhaps, a little more palatable.

In march of 2013, Benriach acquired the “illuminated,” and still somewhat arcane, distillery. It wasn’t long before the new owners set to work doing what they do best–namely, creating some of the most fantastic spirits in Scotland.

That’s right, Dear Reader. I’m not shy about admitting that I am quite partial to much of what Benriach produces – as you can see from my recent review of Benriach’s 35 Year Old offering – in addition to Glendronach, the other distillery that Benriach currently owns. In fact, currently in my cabinet, I’ve got a few single casks of Glendronach that continue to amaze as they open up with a bit of oxygenation.

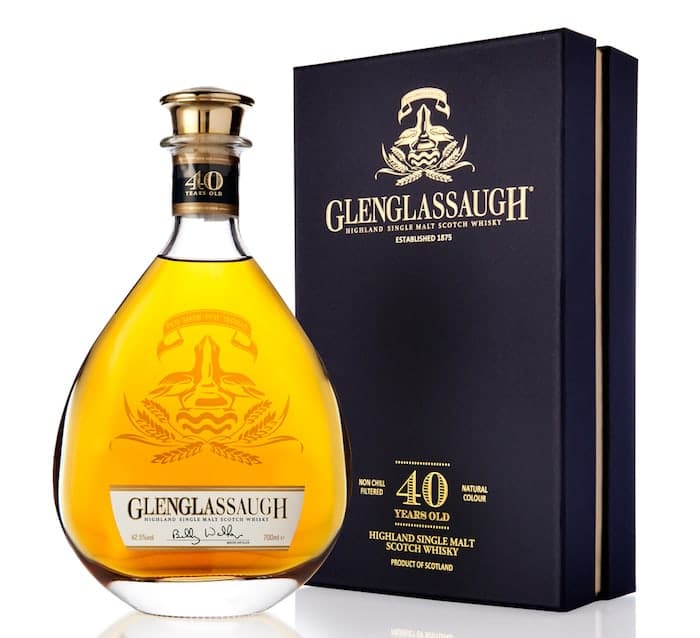

Getting back to the matter at hand…Billy Walker, Glenglassaugh’s Master Distiller, deserves a warm round of applause for the 40-year-old sample that I will be reviewing in my tasting notes (below). Not that he shipped me the sample for free. Au contraire. It was paid for, right down the the last penny. I’m just saying that this OB Glenglassaugh 40-Year-Old is something of an accomplishment–especially coming, as it does, from a distillery with such an intriguing and colorful past.

If one does the math, it’s apparent the whisky in my glass dates back to three years before the United States Bicentennial. As a man of two score years and ten, I can remember 1976 fairly clearly. Those were different days, long before the Internet or cell phones. Apple’s first computer went on sale in July of that year for $666.66. I can recall thinking that it was a pile of plastic junk with a tiny screen, and I laughed at my friends’ parents who had purchased computing machines for such a diabolical price, the value of which, in today’s dollars, factoring for inflation, is $2,838.

At any rate, I’m looking forward to tasting the whisky before me, which was carefully poured, as wash, into casks around the same time that America was getting ready to celebrate its 200 year-old birthday.

Tasting Notes: Glenglassaugh 40-Year-Old

Vital Stats: 42.5% ABV; 40 Years Old; bottled in 2013; 70cl; $1,200-1,500 price window; currently unavailable in the U.S.

Appearance: Deep gold.

Nose: Olorosso in perfectly aged oak beckons: there are Medjool dates, maple walnut ice cream, bananas foster, cracked old leather-bound books, hints of violet–which come and go–raspberries, malted milk balls, an impression of sealing wax…and, last but not least, a phantom note of whole cluster Pinot noir grapes dried in the bottom of a wine glass.

Palate: Delicate syrups roll over the tongue without feeling oily, almost as though it evaporates in media res. However, there is no alcohol burn. To say this dram is smooth would be something of an understatement. I love how the marriage between oak, whisky, and sherry has been consummated over forty long years–a “beckoning fair one,” indeed.

The Oloroso influence seems rather dry in the mouth, evoking jammy figs, apricots, plums, rhubarb. Macadamia nuts are cradled by a ubiquitous yet unimposing oak foundation, which isn’t bitter in the least. The sample in my glass is three quarters gone now. As my mouth and brain have grown accustomed to the broth, I’m happy to report lightly roasted coffee beans, along with Abuelita Mexican hot chocolate. There even seems to be a touch of steamed rice milk with almond syrup. Marvelous, just marvelous.

Finish: Well, the denouement is not what I would call long. In fact, this whisky’s finish is barely medium in length. But a woody-marshmallowy-sweet impression haunts the mouth in the best of ways. I might also add that my dram is really “neat.” By this, I mean to say that a light sprinkling of water does nothing to improve the quality, the depth, or the complexity. Rallfy Mitchell might disagree, with teaspoon in hand, but I really must hold my ground. Lovely stuff–this–at full strength, thank you very much.

Final Thoughts

I suppose the main drawback to this Glenglassaugh 40-Year-Old lies in the fact that it doesn’t present much in the way of a challenge. It’s exceedingly agreeable, smooth, and civilized. The finish is medium-short, and sweet as pie. I’ve read about previous 40-year-olds, released by Glenglassaugh, that sounded far more complex, offering everything from hints of metal polish to pineapple glazed ham.

In other words, there are no savory or industrial influences in this 42.5% bottling. If I were angling to spend upwards of $1,300 on a whisky, I might want a bit more in the way of a challenge. But that’s me. I’m sure that plenty of folks with pockets that deep would rather just sip a delicious dram and think about other things. (Speaking of which . . . in my review of the Springbank 16-Year-Old Local Barley, you will find a discussion of forty-plus-year-old Springbank releases that contain both savory and industrial notes, by the way.)

I also find it interesting that the Glenglassaugh 40-Year-Old is quite a bit lighter in color than the 30-Year-Old. I guess the younger spirit hails from casks with more sherry left in the wood? Darker isn’t always better, however. That’s worth remembering, especially in a very old spirit that has been allowed to retain a decent amount of distillery character.

It’s also worth mentioning that Glenglassaugh has released two batches of venerable old single malts. The first batch includes eight whiskies that range from 28 to 45 years old. The second batch also consists of eight releases, this bunch ranging from 36-42 years old. All of them are reputed to be “fruit bombs.” I didn’t see anything on Glenglassaugh’s website, or in any related whisky reviews online, which pointed to much in the way of savory notes, spicy notes, or industrial notes.

For a distillery that died and came back from the dead more times than I can count, Glenglassaugh sure created a lot of well mannered “offspring.” I’m sure that these bottled spirits are more than happy to “speak their names,” if one holds a glass to one’s ear. They have all the charm of the Belle at the Ball, rather than the Bad Boy who was mothballed.

As for the secret history of an “undead” distillery, I’m relieved to say that this yarn has a happy ending, thanks to Benriach. Slainte mhath. May the river, the tide, and good spirits, rise with you. I have yet to try any of the younger NAS core offerings, but they seem intriguing. Perhaps one or two might stray into the realm of spicy, savory, and industrial.

On the other hand, I’m a sucker for older age statement whiskies that cover all three bases, and then tag home plate (sweet). For me, that sort of complexity is a Babe Ruth-style home run, at least when it’s done right. Judging by the reviews I’ve seen of the discontinued 40 Year Old 44.6% offering, that seems to have been the case. The darkly dangerous broth is rumored to contain spices, smoked meats, and plenty of succulent fruits, as well as chocolaty goodness. Ah, well. The grass is always greener. Especially when the late great Jim Murray tantalizes you with 96 points from beyond the grave. That’s right. A past year of his Whisky Bible gave it one of the highest scores of all time.

Score: 93/100 [SHOP FOR A BOTTLE OF GLENGLASSAUGH 40-YEAR-OLD]

*Note: Portions of this review have been embellished in true Lovecraftian fashion. For instance, the author is not advocating the existence of selkies, nor human contact with them. Neither is the author alleging, unequivocally, that Glenglassaugh distillery has been, or currently is “haunted” by spirits other than those which have been poured into casks. Furthermore, the Old Glenglassaugh Windmill was most certainly NOT constructed by a mad monk in the late Middle Ages. In fact, it’s a beautiful old building, which is a credit to Glenglassaugh distillery, as well as other scenic aspects of the surrounding countryside.

As most people know, quite a few Scottish whisky distilleries’ legends have been embellished, and sometimes even created out of thin air. This review is dedicated to the tall tales that help to make drinking Scotch whisky a lively and fun experience. Part satirical and part factual, it walks a fine line between hyperbole, humor, background information, and tasting notes that were written quite in earnest from a deliciously rewarding 3cl sample.