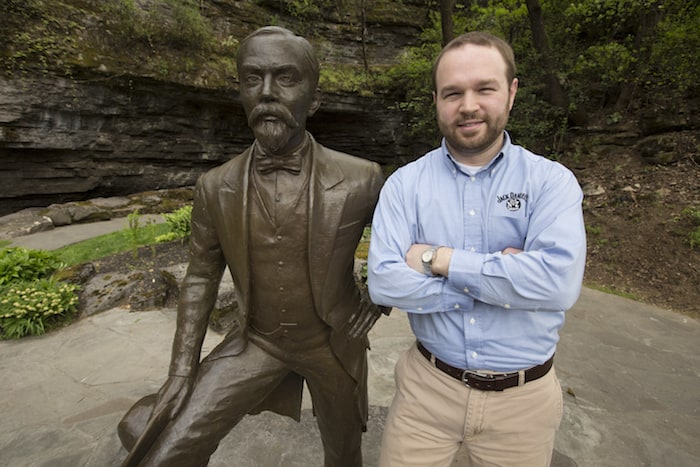

Jack Daniel’s Chris Fletcher oozes a sort of pride in the Jack Daniel Distillery that can only come straight from the heart. Fletcher grew up roaming these warehouses and distillery floors with his grandfather, Frank Bobo, Jack Daniel’s fifth Master Distiller, on the weekends. A child’s wide-eyed wonderment remains just under the surface as he walks through each step of the massive operations where he serves as the distillery’s first-ever Assistant Master Distiller.

Born and bred in Lynchburg and grandson to a Master Distiller, the path to Jack Daniel’s seems a no-brainer. Chris tells a much different story, though, “I really didn’t give a thought of working here.” He had no intention of following in Bobo’s footsteps when he went off to college at Tennessee Technological University in Cookeville and majored in chemistry. “I was two years into it and I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. That’s when 9/11 happened.”

Chris was a sophomore, waiting to go into class when he saw news of the attack on a campus television. At that point, he began thinking his chemistry degree could be applied in the Department of Defense in chemical warfare or something similar. But whiskey is thicker than water and a trip to the Jack Daniel Distillery in the summer of 2012 changed all that. He took his roommate on a tour when he had a sort of epiphany, “Tour guides get paid to just talk.” He decided to take a summer job as a guide because “it was more money than cutting grass and easier work.” By the end of that summer, a new thought occurred to him. “Maybe I could make whiskey.”

After finishing his degree, the call came for Chris to join the team at Brown-Forman, Jack Daniel’s parent company. He moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where he worked in research and development. “It was a great place to start. I learned how to taste whiskey and it all fell into place.” It was there that he first met Jeff Arnett and other whiskey giants like Lincoln Henderson and Chris Morris. After a few years, an opportunity too good to pass up took Chris to Buffalo Trace Distillery where he expanded his experience with the likes of Elmer T. Lee. “Elmer was old-fashioned. He came in and tasted every Tuesday. He knew what he was looking for in his bourbon.”

The ties that bind and the chance to work with Jeff again eventually brought Chris back to his childhood home, Lynchburg. “It’s special to me for a lot of reasons. Jeff is terrific. He’s an open book. He’s a wealth of knowledge. Coming home was an added bonus, but the opportunity to work with Jeff is what made me jump on it.” When prodded on his family ties, he continues, “it was really about 50/50, the legacy and Jeff.”

The “heir apparent” distiller at work

While Fletcher is “heir apparent” to Jeff Arnett, Jack Daniel’s current and seventh Master Distiller, he shies away from assuming the title will next be his. “All of that experience that I’ve had, looking forward, yeah, I hope that I’m number eight here. I do. But there’s no guarantee. It’s something I’ve got to earn. We’ve got a lot of really great whiskey makers.”

All modesty flies out the window as soon as Fletcher turns his focus on the distillery and away from himself. “I don’t know of anyone else doing what we do here,” he explains. “When you talk about ‘craft’ and whiskey made in a traditional way, I say we have nothing to hide. Come see us; we’ll show you everything.” It seems he’s been drilled on the idea of “craft” in the past, and his passion for the craft whiskey that is Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey is clear.

Chris takes me through each part of the distillery, starting at one of the barrel houses and continuing on to the rick yard where a pile of wood is burning into their signature charcoal. He points out that the only accelerant used in making the fire is whiskey, so as not to add any off-putting flavors. We go through an old structure, turned museum, where Jack Daniel’s office and infamous safe are on display. (Jack is said to have died from complications of gangrene and infection after kicking the safe.) He explains the lineage of the distillery’s seven Master Distillers, starting with Jack Daniel, up to his grandfather at number five, to the current number seven, Jeff Arnett.

A quick stop at the cave opening allows time for explanation of the spring water used to make every bottle of Jack Daniel’s. The underwater spring runs throughout the property and even under the distillery. The cave goes back into a hillside about a mile and cuts through layers of limestone, keeping the water at a cool 56 degrees year-round. The limestone-filtered water is an important feature of Jack Daniel’s – it not only removes unfriendly iron from the water, but also adds calcium and magnesium. All cooking and fermentation uses this cave water.

2007 was a dry summer in Tennessee and much speculation was made about the cave water drying up, potentially shutting down the operations at the distillery. On a typical day, the cave water flows at a rate of 2,000 gallons per minute. 480 of those gallons are pumped out into two tanks, one that holds 500 thousand gallons and one a staggering 10 million gallons. This serves as their insurance policy against a drought.

As we move on to a walk through the massive yeast house, Chris explains the process of the yeast mash. Jack Daniel’s employs a full-time microbiologist, Kevin Smith. Smith leads a team that propagates the unique proprietary yeast strain used to make every Jack Daniel’s product. “The jug yeast goes back to Jess [Motlow]. We assume he kept his uncle’s yeast, because, well, why wouldn’t he? For sure we can trace it back to ’38 after Prohibition.” DNA mapping ensures the yeast’s continued consistency. Chris introduces me to “Big Bertha,” a mash cooker filled with cave water, malted barley, and rye. This mash is naturally soured with live bacteria, lactobacillus (also cultured in-house), to protect the mash from contamination.

“Yeast is the number two ingredient in the flavor of our whiskey. Number one is the barrel, obviously, and number two is the yeast.” Here he reminds me that Jack Daniel’s owns their own cooperages where they make all of their own barrels. Just as they raise their own yeast colonies, the distillery also has control of every aspect of the coopering, from the forests they log to the moisture content of the wood to the charring of the completed barrels. Chris returns to the idea of “craft” distilling and says, “these other American whiskey makers, they don’t make their own barrels and they’re buying freeze-dried yeast. They’re not even controlling the two most important ingredients in their process.”

He admits, “A lot of the things that we do, people have chosen to cut out now. Doesn’t mean they’re making a bad product.” Consistency is a common theme in each and every description of all aspects of the operation. Although the distillery has grown and continues to grow, Jack Daniel’s prides itself on each bottle of Old No. 7 tasting the same as the last. “One of the things I very much take pride in is that we make it with the same system, the same process that my granddad did. He started in 1957. Now we’ve got better equipment, more knowledge and more know-how. “

Our tour continues, making our way around the massive 90,000 gallon fermenting tanks into the stillhouse. As we walk by a room full of monitors that I dub “mission control,” Chris explains that all those machines and computers are to aid in consistency. He doesn’t pass up the chance to mention that all of that technology would be for naught. “You still have to have people there that can look at data, take samples and taste.”

Chris and his wife, Ashley, live next door to Chris’s grandfather, Frank Bobo, and Chris mentions him often throughout the day. He’ll be 87 this summer. Of the technology integrated into the plant, he say his granddad would “be the first to tell you he’d only dream he would have the capability we have today.” He goes back to a common thread: “We would be crazy not to make our whiskey more consistent and to a higher standard today than yesterday. If we have the opportunity to make a more consistent product, we owe it to our fans, in 165 countries now, to do it.”

Supplying those 165 countries is an around-the-clock job. The distillery is currently producing about 150,000 gallons, or 2,000 barrels, a day and pulling out almost the same number. The daily production includes mashing a million and a half pounds of corn. Still, the demand is high and the distillery is expanding to meet the needs of the growing sales. Two new stills in a separate facility across the property add an additional twenty percent capacity. The new stills went online in August of last year, but are not yet running at full speed.

We stop for a moment among the huge charcoal mellowing vats before we sit down for a tasting. Chris speaks lovingly of the whiskey, explaining the nuances of each product. He presents the new make whiskey two ways- both before and after the Lincoln County Process. One of the things I begin to understand from that experiment is that the strong corn flavor is being removed from the whiskey very purposefully to allow the barrel to carry a heavier load of the flavoring work. When we get to the honey and cinnamon flavors, Chris says, “today’s Tennessee Honey drinker will hopefully be tomorrow’s Old Number 7 drinker.”

On the topic of new products, I wonder aloud if there have been more new Jack Daniel’s products in the last five years than in the last 100. Chris tells me there was a time when the product line was “pretty diverse.” They once made apple and peach brandies and a one-yea- old whiskey under the Lem Motlow lable. “When Lem started back after Prohibition, he couldn’t wait four to six or seven, maybe eight years to make Jack Daniel’s. He needed some money.”

We talk about some of the new bottles as we sip on an exceptional Single Barrel sample. When asked if he’s working on anything new, Chris hints around. “I am very involved with all the single barrel offerings- the new rye single barrel, the barrel proof. We’re going to have some more things coming down the line, too. Really, really nice whiskeys. Ask Jeff about his ‘baby.'” And I do.