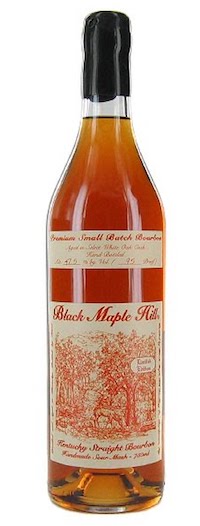

Mention Black Maple Hill to a dedicated bourbon fanatic, and the odds are good you’ll get a response that ranges somewhere from exasperated to enraged. Introduced more than 15 years ago, Black Maple Hill was once a way to get your hands on some very old and rare Kentucky bourbons from pedigreed distillers in a mysterious, atmospheric package. But a couple of years ago, the whiskey in the bottle changed – and according to many, not for the better.

The Black Maple Hill brand was first introduced back in 2000, back before bourbon got really trendy. It’s produced by CVI Brands, a non-distiller spirits importer and bottler based in San Carlos, California. CVI’s portfolio reads like the dustiest, least-frequented section of the liquor store: Cognac, Armagnac, calvados, grappa, fruit brandy, rum, mescal, and a handful of Scotch brands, as well as the odd aquavit, gin, and ouzo. Black Maple Hill is easily its most mainstream product.

For a long time, CVI Brands sourced its bourbon from Kentucky. The early Black Maple Hill releases were said to be (1) wheated bourbon from Stizel-Weller and (2) bottled by Julian Van Winkle III himself. Later, bottling was said to have been moved to Kentucky Bourbon Distillers, and rumor has it the whiskey used came from Heaven Hill. No matter – the magical touch of the Van Winkle finger had conferred an irresistible desirability, and Black Maple Hill bottlings began to sell for thousands of dollars on the secondary market.

But the skyrocketing demand that inflated Black Maple Hill’s prices would prove to be its undoing – or at least its remaking. As the bourbon trend grew, supply of aged stock for their single barrel and small batch offerings, with age statements anywhere from 11 to 22 years, began to dry up. So Black Maple Hill moved to non-age statement, but even then, sourcing was a struggle.

“As time went on, it became very, very difficult to get the aged whiskeys that we needed for the quality. For a while, I was able to do it from Kentucky, but not anymore. So I decided to look around for another source,” said Paul Joseph, owner of CVI Brands, in a recent interview with The Whiskey Wash.

Enter an Oregon craft whiskey distillery

Around the time the mainstream bourbon boom was gaining steam, the Stein family was finalizing preparations to open a craft distillery in Joseph, Oregon, a small agricultural community in the far northeastern part of the state. Stein Distillery was a new venture from a very old business. The Steins are grain farmers – mostly wheat, but also rye and barley – and they’ve been living off the land since the 1890s. Tired of being at the mercy of the commodity grain market, the Steins decided to go the value-added route, and started producing vodka, cordials, and whiskey in 2009.

Today, Stein is a regional craft distillery best known for its aged whiskeys. Its standard lineup includes straight bourbon and straight rye, both in two-year-old and five-year-old expressions, as well as a blended whiskey. All of the grain is sourced from either the Stein homestead or, in the case of the corn, up the road from a cousin in Hermiston. Everything’s distilled and aged onsite in full-sized barrels.

“As soon as I tasted the Stein bourbons and rye, I knew I’d found my source,” said Joseph. “The first thing that caught my attention is that they grew their own grain, so they have 100% control over the quality of their grain, and it’s all local Oregon grain.”

“When I tasted the product, it had a quality to it, a consistent character, which is very difficult to find in small distilleries. I think the world of Dan Stein’s ability; he really knows how to really put together a complete product. And I think people that are knowledgeable about whiskey recognize the quality.”

So CVI introduced Oregon Black Maple Hill in 2014, retaining the old-timey label but subbing in a new, squat bottle shape. It’s the same bottle shape as Stein’s branded releases – which, incidentally, CVI represents in California. The Oregon Black Maple Hill releases don’t carry an age statement, but Paul says they’re made up of casks between four and five years of age, and each batch is usually about 180 six-bottle cases.

We reached out to Stein to comment on their relationship with CVI, but they declined to speak with us.

The “New” Black Maple Hill

The choice to swap craft whiskey from Oregon, of all places, for big-time Kentucky juice left a strange taste in many mouths. It doesn’t help that the Oregon Black Maple Hill bottlings seem to start out at retail around $70 or more, a lot more than even the most enthusiastic consumer tends to want to pay for most craft whiskies.

Is CVI riding on its decade-old reputation as a cult favorite? It seems undeniable. Yet Joesph also seems earnest when he says he picked Stein because he thinks the quality of their products is noteworthy. And based on their portfolio of oddities like grappa, Armagnac, and fruit brandy, all delicious spirits that are totally unsellable to the average American drinker, CVI doesn’t appear to be a company that shies away from a struggle.

But does it work for whiskey fans? CVI says the allocated bottlings remain hugely popular, but message board chatter tells a different story: bourbon nerds seem almost unanimous in their dislike of the Oregon release. That makes sense. In my experience, the kind of consumer willing to drop four figures on a chance to own some rumored Stitzel-Weller juice is quite different than the kind of consumer excited to try some non-age statement craft whiskey made by a young producer from the West Coast.

As a person firmly in the latter camp, and somebody who’d been impressed with Stein’s products in the past, I was excited to sample both current Oregon Black Maple Hill bottlings (bourbon and rye) against Stein’s five-year-old bourbon and rye releases. Are they any different? Or are the Black Maple Hill releases just a more expensive way to get your hands on Stein’s standard product? Here’s what I found.

Tasting Notes: Stein Five-Year-Old Bourbon

Vitals: 80 proof, pricing around $50 here in Oregon.

Judging by the sediment in the bottom of this release, and all three others, I’d guess it wasn’t chill-filtered.

The Test: Stein Five-Year-Old Bourbon is a bit woody in the nose, with pencil shavings, savory grain, and dusty black pepper. On the palate, corn and cola dry out to a spicy, cinnamon-inflected finish leavened with a little menthol. Mild and sweet, there’s not a lot of intensity to it, making me wish it’d been bottled at a higher proof.

Tasting Notes: Oregon Black Maple Hill Bourbon

Vitals: 95 proof, pricing at least $70 at retail.

The Test: Oregon Black Maple Hill Bourbon is much more intense than its Stein-branded brother, with significant barrel character. A chocolatey nose reminds me of unsweetened cocoa powder and stout beer. The palate is also on the roasty side, with a firm, slightly acrid char.

There’s less corn character here, and the whole experience is punchier and more lively – likely a function of the higher proof – but I’m left missing a little fruit or sweetness to balance the smoke.

Tasting Notes: Stein Five-Year-Old Rye

Vitals: 80 Proof, pricing around $50 here in Oregon.

The Test: Stein Five-Year-Old Rye is gentle on the nose without being retiring: floral and spicy, I pick up notes of dark cherry, scented soap, unlit cigar, and a faint suggestion of wasabi. The flavor is quite sweet, with a nice, mouth-filling richness – surprising for a relatively low bottling strength of 40%.

Creamy, buttery notes are complemented by an interesting stalky/grassy element, a bit like green bell pepper. Moderate spice throughout, with a surprisingly long, sweet finish that ends on a wisp of rose petals. Well-balanced and appealing, I like this a lot.

Tasting Notes: Black Maple Hill Rye

Vitals: 95 proof, pricing at least $70 at retail.

The Test: Here, we’ve got a bigger, badder nose than the Stein rye, much more barrel-forward: more wood, more spice, less fruit and flower, with a generic cinnamon and vanilla character.

On the palate, the rye character is somewhat subdued (it could almost pass as a high-rye bourbon). There’s a funny burnt, grassy, resinous taste in the mid-palate, like scorched evergreen wood or the last hit on a mediocre bowl of weed.

I thought water might even things out a bit, but instead it just seems to exacerbate the sappy, grassy flavor, adding a little cinnamon and clove. I don’t love this – in fact, I prefer the Stein-branded version.

Final Thoughts

While I wish Stein’s releases were higher proof, I only prefer the Black Maple Hill Bourbon over the Stein-branded analogue. Of the four, Stein’s five-year-old rye is my favorite, and the only one I’d shell out my own money for (as I have in the past).

As I noted before, the Oregon Black Maple Hill releases seem to be starting at around $70 a retail, but I also found some retailers selling the stuff for $150 or more, which is an outrageous price for these whiskeys. A bottle of Stein’s fine five-year-old rye, on the other hand, costs about $50, a price I consider totally fair.

While part of me thinks it’s really cool to showcase a craft distillery on such a large stage, I worry that it’s a case of too much, too soon. The bourbon collector community is already skeptical about craft spirits, and replacing a beloved brand of super-aged Kentucky bourbon with non-age statement craft whiskey was almost guaranteed to backfire. But hey, at least it responds to the previously levied criticisms that nobody knew where Black Maple Hill’s juice was coming from?

In short: I like Stein. I think their bourbon is alright, and their rye is delicious. I prefer Maple Hill Bourbon to the Stein Bourbon, and the Stein Rye to the Black Maple Hill Rye, but I understand why hardcore fans are disappointed. Whether that’s a sign that CVI has jumped the shark, or a sign that it might be time for drinkers to expand their horizons beyond the overpriced, increasingly hard-to-find super-aged bourbons of yore, is, I suppose, a matter of your perspective.