The 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution, widely known as American Prohibition, passed into US Federal law on the 17th of January 1920.

The National Prohibition Act banned the manufacture and sale of ‘intoxicating beverages’ in the United States. Across the Atlantic, Scotland’s whisky distillers would quickly refer to the unwelcome Prohibition legislation as ‘dry rot’.

For over a decade, from 1920 to 1933, the Prohibition policy divided the United States having been imposed on large segments of American society who had no intention of following the legislation.

Prohibition resulted in rising corruption and the growth of organised crime to meet the illicit demand of America’s alcohol consumers. The closure and loss of the United States’ domestic bourbon and American rye whisky distilleries created a supply void that the scotch whisky industry sought to fill.

This article discusses the fascinating relationship between the scotch whisky industry and prohibition in America and the legislation’s effect on the whisky industry’s development.

Imposing Prohibition

Prohibition emerged from the growing American temperance movement protesting the sale of alcohol in the late 19th Century. By 1915, twenty US states had turned ‘dry’, passing legislation prohibiting the sale and manufacture of alcohol.

State legislation increased pressure for prohibition to be passed under federal law, resulting in the enactment of the National Prohibition Act in 1920.

Across America, bourbon and rye whiskey distilleries ceased production and closed overnight, although the nation’s taste for alcohol refused to vanish.

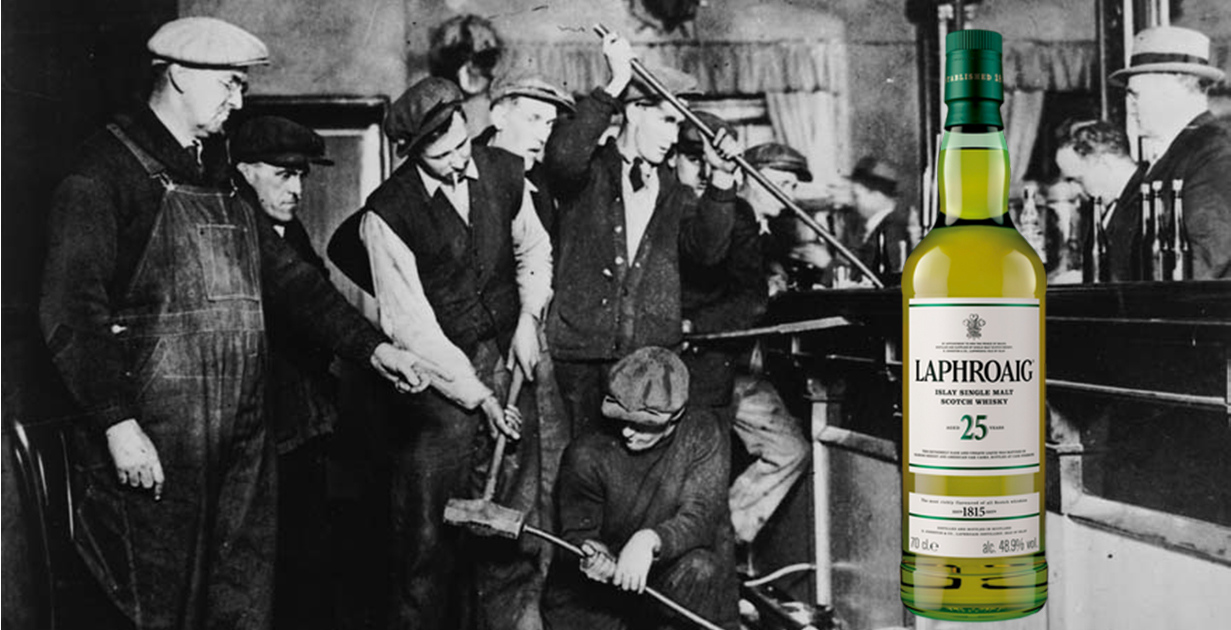

Responding to the challenge of supplying America’s undiminished demand for alcohol, moonshiners began to produce their own liquors, using concealed illegal stills on farms and in woodland, supplying ‘speakeasies’ or hidden bars requiring a password to enter. Due to a high methanol content, moonshine was a dangerous beverage resulting in deaths amongst consumers.

Before the passing of Prohibition, Irish whiskey was a popular American import owing to the Irish heritage of many US citizens. In Ireland, prohibition coincided with the Irish War for Independence (1919-21) and the subsequent Irish Civil War; events which made it near impossible for Irish distillers to produce spirit for export.

The absence of American spirits and Irish whiskey, combined with the dangers of moonshine, increased the demand for scotch whisky in the United States despite its illegality. Fake scotch swept through America, either created by the US ‘Liquor Racket’ (Liquor Mafia) or smuggled into the country from German spirit distillers who produced imitation bottlings of well-known scotch brands, including the White Horse blend.

The founder of White Horse and owner of the Lagavulin distillery, Peter Mackie, successfully prosecuted one German spirit merchant for exporting imitation White Horse whisky. Whilst most Scottish distillers were reluctant to directly break US Prohibition law, the influx of fake scotch and activities of forgers convinced distillers to supply American demand to protect the health of consumers and scotch whisky’s reputation for quality.

Whisky or Medicine? – How Laphroaig Evaded Prohibition

A loophole in America’s Prohibition legislation permitted the use of alcohol for scientific or medicinal purposes.

For centuries alcohol had been used for medicinal purposes and prescribed by doctors as a stimulant, preventative or tonic for illness. American physicians protested the imposition of prohibition, arguing the law infringed upon their right to treat patients. Whilst doctors were permitted to prescribe alcohol during prohibition, the law regulated the amount patients could receive.

Under prohibition, physicians could obtain a licence from the Prohibition Commissioner to prescribe alcohol and were issued a specialised prescription pad from the US Treasury. Every ten days a patient could pay $3 for a prescription from a physician, and then a further $3 to a pharmacist to receive approximately a pint of alcohol.

For American doctors and pharmacists, prescribing medicinal alcohol gave them the opportunity to earn extra money in the era of the Great Depression.

Exploiting prohibition’s medicinal alcohol loophole, some scotch whisky was legally imported into the United States. As Islay’s peated malts are characteristically infused with smoky, briny medicinal flavours in the malting process, Islay’s scotch whisky became the medicinal alcohol of choice for American physicians.

Laphroaig distillery owner and manager, Ian Hunter, famously convinced US customs officials that the Laphroaig malt’s pungent seaweed note was evidence of Laphroaig’s iodine content and medicinal properties.

As the Laphroaig whisky was destined to supply American pharmacists, the US customs officers accepted Ian Hunter’s explanation and allegedly could not comprehend why people would wish to drink the whisky for non-medical purposes.

Iodine deficiency became a widespread malady in the United States during prohibition, prompting the prescription of medicinal alcohol. It was used as justification for the legal importation of Islay scotch whisky from the Laphroaig, Lagavulin and Ardbeg distilleries.

British politician and future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was an ardent opponent of prohibition, ensured he was provided with a prescription for medicinal whisky during a visit to the United States in 1931.

Scotch Whisky: Controlled Bootlegging

The quantities of legally imported scotch whisky were more than what was required to meet medicinal needs but fell far short of meeting the full demand of American consumers.

Unwilling to provoke the wrath of the US Government, scotch whisky distillers targeted exports to neighbouring countries and territories unaffected by Prohibition including Canada, Mexico, the West Indies and St. Pierre and Miquelon. In 1922, exports of scotch whisky increased by 400% to Canada and the West Indies, by 4000% in Bermuda, and a staggering 40,000% in the Bahamas.

The French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon imported 119,000 gallons of scotch in 1922, an enormous amount considering the territories’ combined population was six thousand people. From these countries, vessels laden with scotch whisky departed for America.

The practice known as ‘rum running’ saw vessels halt their journey just beyond US territorial waters and off-load the cargo onto the speed boats of American bootleggers, who evaded the coast guard to deliver scotch to the mainland.

Scotch distillers feared that due to increased demand American bootleggers might tamper with or ‘cut’ the whisky, diluting the spirit to increase supplies before reaching consumers. The Distillers Company Limited (DCL) united with prominent independent scotch distillers to form the ‘Scheduled Area Organisation’ which established a form of controlled bootlegging.

Customers and bootleggers who breached the regulations imposed by the scotch Whisky Industry’s ‘Scheduled Area Organisation’ by ‘cutting’ spirit were deprived of supplies and credit.

Despite the regulations, the illicit liquor trade was operated by organised crime in the United States, with crime bosses including Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano and Frank Costello amongst the prominent customers of the scotch whisky industry.

A significant figure of the prohibition era who boosted the popularity of scotch whisky in the United States was William ‘Bill’ McCoy. A former merchant navy sailor, McCoy entered the illegal ‘rum running’ trade, concealing up to five thousand cases of whisky on his schooner ship, the Arethusa, or by piloting speed boats evading US Coast Guard patrols.

McCoy was meticulous in ensuring the quality of the liquor transported, preventing the tampering and ‘cutting’ of spirits. McCoy’s reputation for protecting quality led him to partner with prominent distillers and spirit merchants in the transportation of whisky to the United States.

The expression ‘The Real McCoy’ allegedly originated amongst bootleggers to describe the genuine spirits and liquors transported by William McCoy.

The End of Prohibition

By 1930 the Scotch Whisky Industry’s involvement in bootlegging had become an open secret, akin to the continued alcohol consumption in the United States. The British Government made little effort to stop the Scotch distillers from exporting whisky destined to be smuggled into the US.

At a Royal Commission hearing Alexander Walker, of John Walker & Sons and the Johnnie Walker brand, famously stated that he would not cease the export of spirits to the United States even if he could.

In America prohibition grew increasingly unpopular; the rate of alcohol consumption was estimated to have risen despite the ban, whilst organised crime groups grew wealthy and powerful from the smuggling and distribution of illegal alcohol, leading to cities such as Chicago becoming mired in corruption and violence.

In 1933, the National Prohibition Act was repealed at the federal level, with the decision to retain prohibition left for individual states to determine. In the decade over which prohibition was enforced American bourbon and rye whisky distillers had lost a generation of expertise and knowledge, impeding the recovery of the United States’ domestic distilling industry.

Scotch whisky retained its popularity and reputation within America; before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1938, the formerly ‘dry’ United States accounted for over 60% of the Scotch Whisky Industry’s overseas export market.

Prohibition also impacted Scotch whisky distillers, predominantly in Scotland’s historic whisky capital of Campbeltown. There was an initial boom across the Campbeltown whisky industry as distillers sought to supply American demand.

However, over time the majority of the region’s distillers ruined their reputations by producing hurried whiskies for the US by running the stills quickly to distil large quantities of low-cost spirit.

Once Prohibition was lifted blenders and spirit merchants began to seek out malts of better quality elsewhere, triggering the eventual collapse of Campbeltown’s whisky industry.

At the beginning of the 1920s twenty distilleries were operating in Campbeltown; following the repeal of prohibition, only Springbank and Glen Scotia remained operational with both distilleries attaining cult status amongst whisky enthusiasts.