Editor’s Note: This article continues a series of pieces we will have over the next few months focused upon the different major Scotch whisky regions. So far we’ve also touched upon the Highlands, Speyside and Campbeltown.

The terrain of the Lowlands is characterized by undulating fields, which are ideally suited to growing grain for whisky. The less rugged landscape is reflected in the region’s single malts, which are lighter in both color and body than those of the Highlands. With little or no peat used in the drying of the malted barley, the whiskies distilled here are naturally fresh and light, fragrant and flowery, with cereal and biscuit flavorings. They make ideal aperitifs.

Producers of Note

Glenkinchie and Auchentoshan are the two better known distilleries producing and releasing bottled whisky in the Lowlands. Glenkinchie’s rustic location amidst fields of barley, and a mere twenty-mile distance from the capital, makes this “the Edinburgh Malt.” Its light character is the result of its distillation in some of Scotland’s largest stills. Matured for 12 years, it produces, a distinctive light whisky, typically of the Lowlands, with a soft creamy texture.

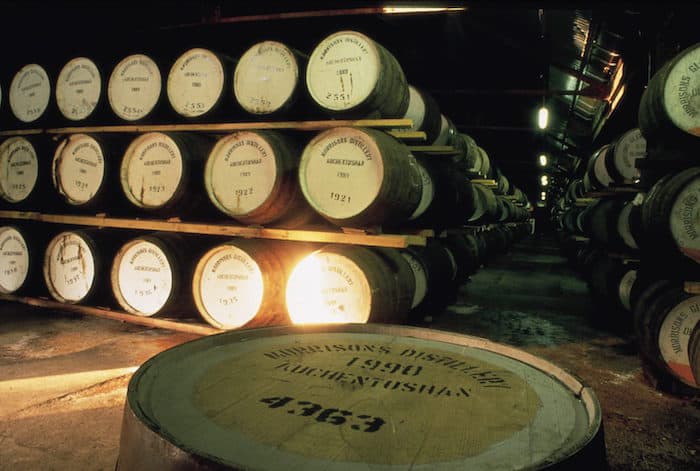

Dating back to 1825, Auchentoshan meticulously ensures that their whiskies are triple distilled. The result is a silkier, smoother whisky that gave rise to its nickname, “breakfast whisky.” Blind tastings have consistently shown that the distinctive smoothness is very noticeable and is a defining signature of this whisky. The Auchentoshan house style is light and smooth, with distinctive floral and citric notes.

Ailsa Bay, part of the grain-distilling complex at Givran, began operations in 2007 and released its first bottling in February 2016. Uncharacteristically for the region, this is a heavily peated whisky that has a distinctive sweet and smoky profile, but one in which the phenolic medicinal notes have been minimized. Bladnoch, formerly in receivership, was bought by Australian entrepreneur David Prior in July 2015, and is in the process of restarting its distillation operations.

Bladnoch is one of the oldest distilleries in Scotland, having been founded in 1817 by Thomas and John McClelland. It went through a variety of owners before ending up in the control of United Distillers in 1987. It is the southernmost of all of the Scotch distillers and is characterized by a light, sweet, grassy, and floral style. Some of the older bottlings are also notable for their distinctive citrus/lemon note.

Two more distilleries are currently operating but have not yet released any bottlings. Daftmill began operations in 2005. Annandale began distilling operations in 2014 and is expected to release its first bottlings in 2018. The Glasgow Distillery Company is planning a new distillery in the city center of Glasgow. In addition, malt from six other Lowland distilleries is available: Rosebank, Kinclaith, St. Magdalene, Ladyburn, Inverleven, and Littlemill, although the distilleries themselves are no longer active.

Lowland History

During the eighteenth century, the distilleries in the Lowlands were increasingly geared to the production of spirit intended for rectification, i.e., further distillation, into gin. Immediately following the Act of Union in 1707, they had a distinct advantage over the more heavily taxed British distillers.

Since distillation in England was based on wheat, the increased demand for wheat, along with the corresponding increases in prices, was in the interest of the landed aristocracy. The result was continuing pressure on Parliament to protect the British gin distillers, and by extension the aristocracy and their estates that were supplying them with wheat, and to raise duties on the Scottish Lowland distillers. The fact that at the same time Parliament was also looking for more revenues to fund its wars with France made for a convenient pretext.

The response of the Lowland distillers to rising taxes was to produce ever-more quantities of spirit in order to amortize the tax on capacity against ever-higher levels of production. The Wash Acts had assumed that the typical Lowland distiller would charge his stills an average of once a day. By changing the design of their stills, however, the Lowland distillers were able to cycle their stills an average of ten to twenty times a day. Some distillers were able to cycle their stills two to four times faster than that. The result was a flood of cheap spirit. It was horrible whisky, however, having little in common with what was being produced in the Highlands, and only fit for rectification into gin.

There was one other issue that was also shaping government policy and that ran counter both to the interests of Parliament for tax revenue and those of the British landed aristocracy—the pressing need to combat rampant alcoholism from cheap gin. The consumption of gin in London had reached 3.5 million gallons in 1727. By 1735 it had risen to 5.5 million gallons. This was a rate of consumption of two pints per week per inhabitant. The British government saw the gin craze as a primary cause of rampant crime and as a serious threat to the fabric of British society. Starting with the Gin Act of 1729, Parliament passed a series of “gin laws”—the Gin Act of 1736, the Sale of Spirits Act of 1750, and the Gin Act of 1751—to restrict and regulate the sale of gin.

The Lowland distillers, principally the Haigs and Steins, the first whisky dynasties, had started sending whisky to London for rectification into gin in 1777. Although it is likely that lowland distillers were exporting whisky to England before then. This was the first officially recorded export of Scotch outside Scotland.

By 1786, Scottish distillers controlled a quarter of the London gin market. Responding to pressure from the British distillers, Parliament had passed the Scottish Distillers Act in 1786. The new higher duties on exports to England effectively shut down the Lowland distillers. Export sales declined by more than 90 percent, and many Lowland distillers were driven into bankruptcy.

The end of the Napoleonic wars eliminated Parliament’s pressing financial needs. It was also clear by then that the regulatory system that had evolved since 1707 had produced chaos, rampant illicit distillation and smuggling, little effective regulation, and not much tax revenue. In 1816, one year after Waterloo, taxes on whisky were cut to a third, and the use of smaller stills was again allowed in the Lowlands.

Following a lengthy Royal Commission, Parliament passed the Excise Tax of 1823. Taxes were again decreased, and most restrictions on the production and export of whisky for licensed distillers were eliminated. Duties were levied at the rate of 12 pence per gallon for stills with a capacity of more than 40 gallons. In addition, there was a licensing fee of ten pounds sterling.

The act represented the first attempt to enact legislation that would both promote legitimate distillation while ensuring reliable tax revenue for the government. Following the passage of the 1823 Excise Act there was a significant increase in the number of licensed distillers, primarily in the Lowlands. The modern Scotch whisky industry was about to be born.