Like litters of puppies and kittens, hundreds of line extensions squeeze out of distillery bottling plants annually, especially from NDPs and small distilleries eager for attention.

By comparison, Maker’s Mark waited 57 years to create a single permanent line extension until the 2010 release of Maker’s 46. As the first of the distillery’s seasoned-stave wood finishing line, it gave birth to the Private Selection program while providing ersatz permission for the rollouts of Maker’s Mark Cask Strength and 46 Cask Strength.

Believing more innovation might be good, Maker’s hired Jane Bowie 15 years ago—first as a brand ambassador, and then as disruptor who’d dare ask, “Why do we do the things we do here?” At Maker’s Mark, the pat answer to such queries is, “Because we’ve always done it that way.” But as Maker’s master of maturation and director of innovation, Bowie’s tasked with testing such replies.

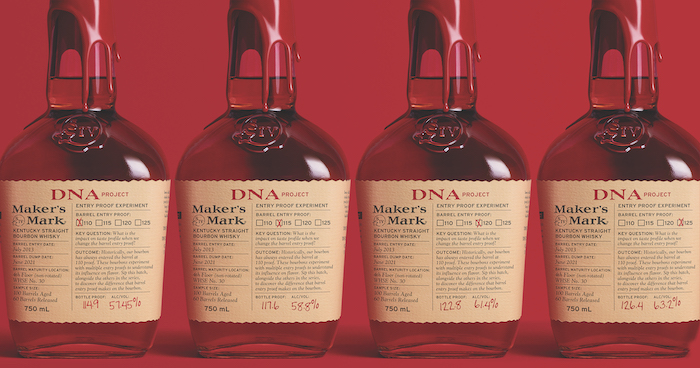

Under the heading of the DNA Project, she and innovation manager, Beth Buckner, (“She’s chemistry geared, data driven,” Bowie says, before adding, “And I’m sensory-geared.”) set out to discern whether Maker’s Mark’s 110 barrel-entry proof was truly the ideal number. “’Cause we’ve always done it this way” wasn’t a good enough reason to keep doing it, so they created the Barrel Entry Proof Experiment to test it.

* Suffer me this small aside: Am I the only one amused by the Orwellian-bland names of Maker’s line extensions? FAE-01, 46, RC-6, 101, etc., sound more like names of Star Wars sidekicks than bourbon names. Yet when the bourbons for which they’re named are delicious, why change?

Back to the DNA Project and the Barrel Entry Proof Experiment: Eight years ago, Bowie and Buckner took a 100-barrel lot and broke into four groups of 25 barrels each. The whiskey made to fill them originated as mash from multiple fermenters turned into whiskey from a single distillation run. That 130-proof distillate was gathered into a single cistern and cut to proof in steps: 125, 120, 115 and 110, with each proof occupying 25 barrels.

And since she was already asking “why?” questions, Bowie departed from Maker’s standards two other ways: All 100 barrels were stored in the middle (fourth floor) of a single rickhouse (not rotated from higher to lower floors as is the brand’s custom), and aged eight years instead of five to seven.

While the whiskey rested, Bowie took her barrel-entry-proof questions to other sources, notably Michael Veach, American whiskey historian and author. When asked why he thought 110 proof was Bill Samuels’ preferred barrel entry target, Veach said whiskey makers long ago employed lower barrel entry proofs in hopes of yielding maturate at drinkable proofs.

“Before Prohibition, whiskey was sold from the barrel it was aged in, so they wanted to sell whiskey as close as possible to the proof that customers liked to drink it,” Veach said. After Prohibition’s end, barrel entry proofs rose in modest steps as distillers sought to cut costs by using fewer barrels. When the legal maximum entry proof of 125 was established in 1964, Veach said “some distillers took advantage of that opportunity to raise entry proofs … though many stayed at lower proofs for a long time because the results were better.”

Water, Veach continued, extracts vanillin, caramel and wood sugars from the barrel in greater quantities than does alcohol. Whether Bill Samuels understood how each liquid worked isn’t clear, he said. But what’s known is Samuels was an experienced distiller (founder of T.W. Samuels Distillery) who knew what worked well, and he kept doing what he’d always done when he started Maker’s about a decade after leaving T.W. Samuels.

In July, when Louisville’s Bourbon Society held its first face-to-face meeting in more than a year, Bowie let the group taste the results the Barrel Entry Proof Experiment.

“This is the first time anyone outside of Maker’s Mark has tasted this,” she said. “Whether that means you’re lucky depends on if you like it.”

In front of each guest were four Glencairns holding pours of each 8-year-old cask strength whiskey. (My own notes accompany each.)

- 110 entry proof was dumped at 116 proof and yielded a sturdy, stout and rich whiskey with a dry finish.

- 115 entry proof was dumped at 117 proof and yielded a whiskey that was deep, dark and heavy with caramel but tight on the palate (to me, regular Maker’s moves about the mouth easily). Bowie said, “To me, this one has taken a lot of the wood goodies and muted them.”

- 120 entry proof was dumped at 122 and gained dark fruit and caramel, but the traditional Maker’s sweetness was gone.

- 125 entry proof was dumped at 126 and produced a bold, slightly tannic, robust whiskey lacking nuance.

“You may have liked any of them, but if I hadn’t told you where these came from, I doubt any of you would say, ‘That’s Maker’s Mark,’” Bowie said. “You may like the 120 entry proof, but it’s not Maker’s Mark as we know it and love it. And that’s not good enough.”

Ultimately, Bowie said, the goal was to learn “what would happen if we did this or that. And we learned that 110 is the right entry proof for Maker’s Mark.” She allowed that her findings weren’t earth-shattering, but she said the exercise of answering those “why?” questions confirmed that the historic practices set up by Maker’s founders were correct.

“When we innovate, we do it within established guardrails that guide us and keep us centered on the founders’ taste vision,” she said. “We have the resources to conduct these kinds of experiments, so why not do them and learn?”

Wondering what happened to the whiskey used in the experiments? Fifteen barrels of each 25-barrel group will continue aging for future research, but 10 barrels of each group were bottled for gift shop and select retailer release in late August. By the time you read this, it’s likely those 9,600 bottles (priced at $99 each) will be gone.

If you think that information is a cruel tease, then please accept my apologies. No malice intended. Truth be known, I side with Bowie: Tasting those experiments was fun, but I doubt I’d enjoy a full bottle of any of them. Maker’s Mark whiskeys are like beauty pageant contestants: pretty, elegant, polished and poised. These editions, while flavorful and fun to taste, were rough around the edges and lacking those mannerly qualities of the bourbons bound up in those red-necked bottles. I’ll stick with the originals as we await other experiments.