At first glance, the 20th century categories of gin and whisky could not be further removed – one is for the most part un-aged, clear, distilled to a high-proof, then heavily rectified and flavored with external ingredients; the other almost the exact opposite in every sense. But were such distinctions always such clear lines in the sand? A throwaway comment by a talented bartending colleague with a shared interest in the history of drinks inspired me to pursue this train of thought to a surprising conclusion, especially relevant in this current age of gin ‘boom’.

Whilst diving headfirst into classic recipe books by legends like Harry Craddock and Jerry Thomas and wallowing in their decadent fin de siècle libations, my friend happened to muse that we should be careful when attempting to recreate their concoctions, as many of the core ingredients they were using could well be very different (if not entirely moribund) today.

The first, and most obvious, case-in-point is that spirits we are very comfortable and familiar with nowadays such as tequila and rum are almost entirely absent from the pages of 19th century collections (and only really appear in later post-prohibition classics such as The Savoy Cocktail Book or Old Waldorf Bar Days from 1931). More remarkably, the now-ubiquitous vodka is also conspicuous by its rare appearance (only gaining explosive and rapid favor in the post-Second World War 1950s – Mr Bond and the rapid emergence of globalization have a lot to answer for in the that regard).

This leaves us with a relatively shallow pool of base ingredients from which history’s master-imbibers had to work: effectively gin, whisky and brandy (along with the limited brands of liqueur, aperitif and digestif available). Given the decimation of the latter category in the 1860s following the Phylloxera epidemic, the huge burden of responsibility for refreshing society’s palates was placed on gin and whisky.

My interest in this was further piqued during my time working as a trainer for both Jack Daniels and Bols Genever whilst in the UAE. Both Bols and Brown-Forman were generous with their supply of ingredients from various production stages, such as charcoal, wood staves and, most importantly, the liquids themselves. I was immediately struck by the similarity in nose and palate certain stages of them shared, which was quite eye-opening. In blind-taste tests, training groups of up to 50 were often unable to differentiate the two.

Both categories had enjoyed three or four hundred years of evolution up to this point, with noted key dates such as 1495 in the whisky world – when the Friar John Corr was famously quoted as stating, “to make aqua vitae, VIII bolls of malt,” referring to whisky for perhaps the first time in print – and the third Gin Act of 1751 ,which imposed quality control and an approved list of high-quality botanical sources.

However, prior to the 19th century, it is a fair supposition that gin and whisky shared far more similarities than differences. Both were pot-stilled, both were most-often un-aged and, for many years, neither were averse to the addition of herbal flavorings to soothe an aggressive spirit, with whisky making in Scotland being famously unregulated and made amidst a constant game of cat-and-mouse with English tax collectors.

“In 1823 the English government introduced a new Act reducing the outrageous excise tax levels that made it possible for enterprising Scots to come out of hiding and legally produce and sell their beloved Whisky” (Bottle of Glenlivet, 1990)

Thus came the first of three developments in the 1800s that saw the categories skew in different directions. Following the excise act, the invention of Aeneas Coffey’s Patent Still in 1831 enabled, for the first time, the ‘pure’ neutral spirit we now associate with white spirit categories such as gin. Prior to this, both whisky and gin would have been most often pot-stilled in small batches and intensely grain flavored as a result.

Blending whisky became legal in 1860 to complete the triumvirate of industry shaking influences, and the growth of scotch to fill the vacuum left by Phyloxera-struck European brandy industries such as cognac and armagnac laid the foundations for the category we now enjoy over 150 years later. The final twist in the tale of the divorce of gin and whisky came as late as 1910 when a law was first passed requiring whisky be aged for at least two years (increased to three in 1920).

We were less than ten years away at this point from the passing of the Volstead Act of prohibition in the United States that sent ripples through the world of spirits and cocktails that we are still feeling the effects of today. The ten years it was in effect saw still more blurring of the lines as standards were rocked by the illegal production and import of both categories, be it ‘bathtub’ gin or poorly-made whisky imported across the Canadian border. This period in effect regressed the evolution of both spirits to a state comparable to the excesses of London’s Gin Lane in the years preceding the Gin Act of 1751, when intoxication trumped quality at every turn.

In the modern drinking world, serious imbibers of quality liquor very much embrace the tenet of, ‘drink less but better,’ but within this civilised mould are we seeing signs of the star-crossed lovers of gin and whisky making moves toward reconciliation?

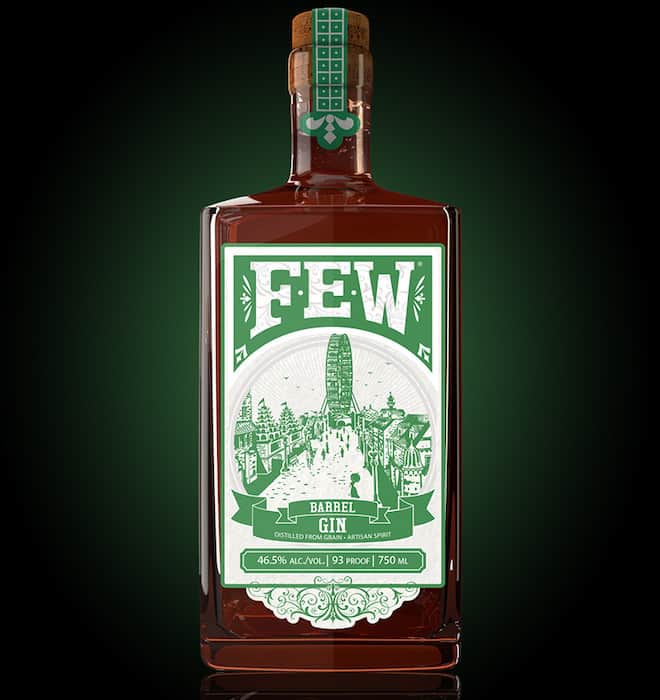

Barrel-aged gins such as FEW from Chicago, Ransom Old Tom and Burrough’s Reserve from Beefeater are gaining increased respect and attention. Meanwhile un-aged whiskies such as American White Dog by the likes of Maker’s Mark (Maker’s White) and Heaven Hill (Trybox Series New Make) garner increasing praise and column-inches.

If the magical gin-affiliated word ‘botanical’ was ever to make an appearance in the world of whiskey, would the act of osmosis be complete and the walls of difference pulled down entirely? In the ever-expanding, paradigm-challenging world of prestige spirits, would this be an admirable progression or a travesty to be resisted at all costs? Should the twain of gin and whisky never meet, or is the center ground ripe for exploration? I shall keep my glass at the ready to find out.