In 2014, Dewar’s introduced the American market to Craigellachie with the launch of its “Last Great Malts of Scotland” range, which showcased several previously underexposed distilleries. But many of us had been acquainted with Craigellachie for some time, even if we didn’t know it, since its malt makes up an important component of several popular blends, including Dewar’s White Label and Johnny Walker.

Craigellachie is famous for its uniquely savory flavor profile, the product of a distilling process that, from start to finish, aims to preserve some portion of the sulphurous compounds many distilleries go to great lengths to excise. And after tasting Craigellachie’s 13-year-old single malt for the first time last year, I was excited to visit the distillery to see for myself exactly how that peculiar meaty flavor comes to be.

The distillery takes its hard-to-pronounce name (it’s “cruh-GHEL-uh-hee,” not “CRAIG-uh-LACK-ee,” as I was informed by a bartender at the nearby Highlander Inn after trying to order the stuff) from its location in the village of Craigellachie in central Speyside. Unlike many Speyside distilleries, Craigellachie isn’t tucked away down a winding single-lane track, surrounded by sheep fields. Instead, it’s right on the main road, with nary a gift shop or visitors’ center to be found. It’s a no-nonsense production space fitting for a malt that, for many decades, played an entirely behind-the-scenes role.

We arrived at Craigellachie in the early afternoon, where we met distillery manager Keith Brian. Craigellachie isn’t open to general visitors, so the experience here is quite a bit different than some of the more tourist-focused operations. After donning our high-viz orange vests, we headed into the production space. First stop: malt storage. Keith points to several multi-story grain storage bins and explains that the Craigellachie distillery actually seeks out malt with a high sulfur content (created by kilning the malt with coal).

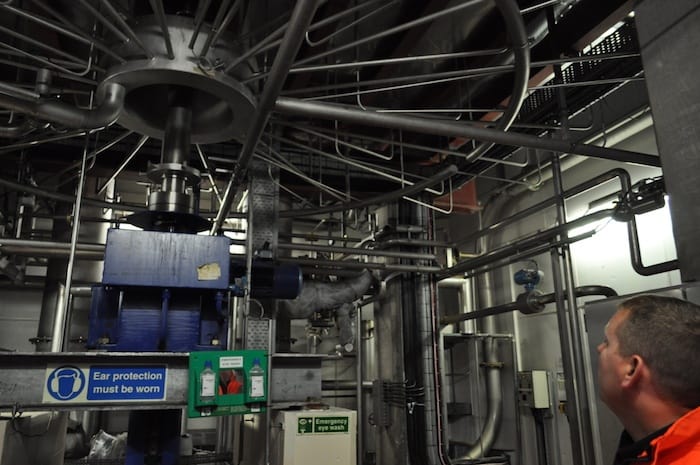

From the mill room, we passed through an unmarked door into a little-seen part of the distillery: the space directly underneath the mash tun. Looking up, dozens of pipes are visible radiating out from the mash ton like a medusa: narrow ones for wort, wide ones for draff. It’s a modern German design, and nearly fully automated, in contrast with the still house, which is still fairly manual and hands-on for the stillman.

Upstairs, we view the mash tun from a different, more conventional perspective. It’s located in the former kiln, with the interior of the Doig pagoda on full display, and is so large it takes up almost the entire space, with just enough room for workers to scoot around the edges. Like many other distilleries, Craigellachie has grown like a hermit crab inside its original building, changing the way it uses its space as technologies evolve and businesses grow.

The wooden washbacks are likewise tightly packed into the adjacent fermentation room—Craigellachie is using every square inch of its urban-for-Speyside space—and the aroma of the fermenting wort already has some of those rich, savory notes I know in the finished whisky. But it’s not until we visit the stillroom that the presence of sulphur makes itself known, visually as well as olfactorily.

Craigellachie’s stills are large and relatively squat in shape, with short, stubby necks and sloping shoulders. The still house has four stills, two wash and two spirit, which are similar in size and shape. The wash stills are nearly black in color, indicating the presence of atmospheric sulfur from the alcohol vapors, which causes copper to form a dusky patina. We watch the stillman carefully polish the bright, brassy door to the wash stills, heightening the contrast.

For the final, sulfury coup de grace, we ascend a flight of exterior stairs to take a look at the worm tubs, Craigellachie’s old-fashioned condensers. To the untrained eye, they don’t look like much, just three square tubs filled with murky water, but they play a critical role in leaving in just enough of all that sulfur the distillers have worked so hard to create. Under the surface of the water sits the worm, a twisty copper tube that gently cools the vapor exiting the stills. It gives the vapor much less contact with copper than more modern shell-and-tube condensers, which means more sulfur left in the final product.

Having the tubs outside helps to dissipate the heat and cool the water, but also means they are more sensitive to the weather, one of the reasons why the traditional distilling season included downtime during the height of summer when it would be hard to get the water cool enough to operate efficiently. The worm tubs themselves also require a lot of maintenance, as the cast-iron exterior is prone to rust and any leaks in the worm require the tubs to be drained and distilling to stop until they can be detected and repaired. Yet the flavor they add to the whisky is viewed as being worth the expense, and I hope Bacardi preserves this piece of working history.

Craigellachie’s single malt may not be for everyone, but it seems to be for many. Our guide informs us that the 13-year-old single malt is on allocation in Scotland, even at the Dewar’s employee store. 17-year-old and a 33-year-old expressions have also made appearances in the U.S. market (I even spotted one at the airport!). Yet Craigellachie still sells the vast majority of its whisky to blenders, who can’t replace its resonant bass note with any other malt.