There’s a bit of a stir recently over aging Irish and Scotch whisky in American barrels. Distillers are in an experimental mood, whisky traditionalists are stamping their feet, and customers are queuing up, sampling, and buying.

You may be wondering: What’s the big deal? Irish and Scotch whiskies have been aged in ex-bourbon barrels for decades, they’re used more than the increasingly expensive and hard-to-source sherry casks these days. How is this experimental?

Because the barrels we’re talking about either aren’t ex-bourbon, or they aren’t even ex-. Distillers in Ireland and Scotland are spicing up their whisky with time in ex-rye casks, and giving it the full-on virgin oak treatment that American whiskeys get (as required by American law). That’s most definitely a new thing, or two new things.

What’s driving this? Fairly simple things, most likely. First, there is a definite upswing in the number of used rye barrels coming out of the American whiskey industry. While craft brewers have been snapping them up for aging beers, it was only a matter of time before the traditional buyers of the industry’s used barrels got into the act. American distillers produce a steady and reliable stream of the used whiskey wood that Scottish and Irish distillers need, and rye makes for an interesting difference.

That’s the second reason: difference. As has been the case in craft beer for years, the retail whiskey trade has become about ‘What do you have that’s new and different?’ Wine finishes, new types of malt or grains, different aging regimens, opportunistic one-offs like Buffalo Trace’s E.H. Taylor “Tornado Surviving” bourbon: they’re all designed to offer the strongly curious and perhaps somewhat jaded consumer something new to try. Rye barrels are now available in sufficient quantity to make a rye cask finish possible.

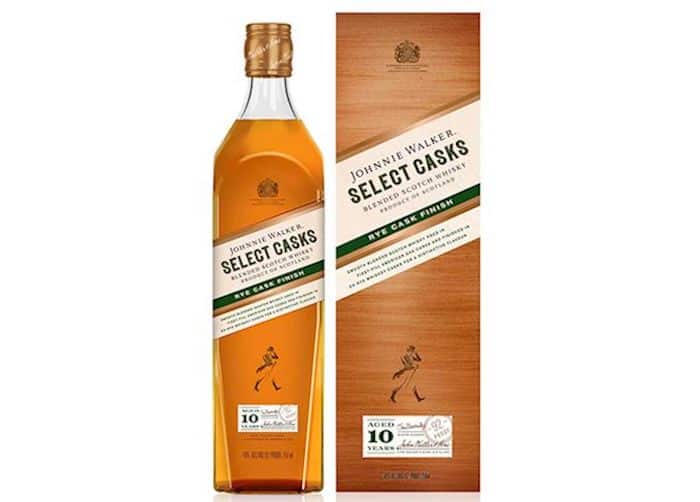

Perhaps the biggest splash was made by the Johnnie Walker Rye Cask, first in a series of “Select Cask” bottlings. The “select” part is indicative of the limited nature; while there are more rye barrels available these days, there still aren’t Johnnie Walker-level numbers. How is it different? It’s bottled at 46% ABV, not the 40% that’s normal for the JW portfolio, an indicator of the intent for it to go in cocktails, somewhere Scotch has not heretofore had a lot of luck with outside the standard Scotch-and-soda highball.

There are smaller splashes as well. The Dad’s Hat Rye brand (Bristol, Pennsylvania) just announced that they have shipped freshly-emptied rye whiskey barrels to the craft-sized Isle of Harris distillery in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Isle of Harris will be aging their malt whisky in them, looking for the same results as Johnnie Walker.

What are those results? Imagine malt whisky – creamy, sweet, nutty – with the spice and enticing bitterness of rye. Some tasters also pull out vanilla from the oak, and a brininess that’s more common in peated Scotch. It’s an experiment that’s worth watching over the coming years as more distillers play with it.

Virgin oak barrels are an easier difference to engage, as all a distiller has to do is order up some bourbon-style barrels from the cooperage: white oak, air-seasoned, with a #3 char. Such barrels were previously dismissed by the traditionalists as overwhelming to the more delicate character of malt whisky, but a judicious use of them in the blending process is proving to create a whisky that is meeting drinkers’ tastes.

Irish Distillers, the folks who make Jameson, have been ahead of the curve on wood research, and it’s not surprising that they came to the virgin oak process early on. Aging their sweet spirit in unused bourbon-type barrels – what they call “BB-0”, to indicate ‘Bourbon Barrel, used zero times’ – gives it a firm foundation of vanilla and coconut characteristics to support the usual fruitiness of the whiskey.

It’s a trick they use in both the Jameson Gold blend and the single pot still Barry Crockett Legacy, but as part of the blend of barrels going into the whiskey, not all. Master distiller Billy Leighton notes that the new oak provides hints of spicy new wood, toasted oak, and vanilla that intertwine with the contributions of the other casks. The Jameson Whiskey Makers series also features a new oak entry, the Cooper’s Croze, a project of their renowned head cooper, Ger Buckley. It blends new oak aging with conventional ex-bourbon and ex-sherry wood.

And yes, Scotch whisky’s doing it too, even as mainstream a name as Glenfiddich. Malt master Brian Kinsman has put together the 14 year old Bourbon Barrel Reserve, a whisky aged 14 years in ex-bourbon casks, then finished in “deep charred new American oak barrels.” The finish yields richly sweet toffee with notes of wood spice and yes, vanilla.

Which brings up the concerns over this practice: does it make every whiskey taste too much the same; i.e., like vanilla? And is new oak, which helps age bourbon so much faster than Scotch, being used mainly to speed the aging of whisky in an industry that’s almost desperately short of well-aged stock?

These are valid concerns, especially as some whisky watchers are wondering if the general trend of Scotch is toward a popular middle. The rye finish would seem to steer clear of that issue (though many purists still decry the whole idea of “finishing” whisky), but the use of virgin American oak does put an emphasis on the development of wood character over distillery character.

The best way to guard against this, of course, is to drink widely, purchase accordingly, and speak up. Whisky companies have proved that they’re listening by giving us more different bottlings, so let’s see if they’re willing to listen on this topic.