Following up from Part 3, in the second half of the 19th century, America was buffered by a series of economic boom-and-bust cycles before cruising into the Progressive Age. Despite financial waves of prosperity and shortage, agricultural progress led to large scale efficiencies in cereal cultivation, the industrialization of the economy and new transport systems, all benefiting the whiskey industry. New energy sources such as steam power, later electricity and petroleum sped the new industrial age into mass-production with cheaper goods. The population doubled between 1870 and 1900 as immigration surged and urbanization created unprecedented consumer demand.

An expanding railroad network carried cheaper raw materials to distilleries, allowing new industrial-scale distilleries to embrace the latest mass-distilling technologies in the mid-West. The American thirst for lager beer and whiskey was insatiable as temperance and prohibitionist activists closed venues, and six States banned liquor sales. The cycle of economic contractions squeezed liquidity for over-leveraged distilleries, forcing many into insolvency or amalgamations. The fate that befell Taylor distilleries.

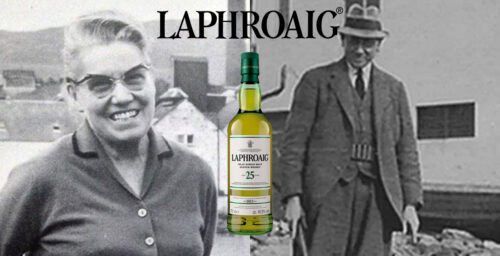

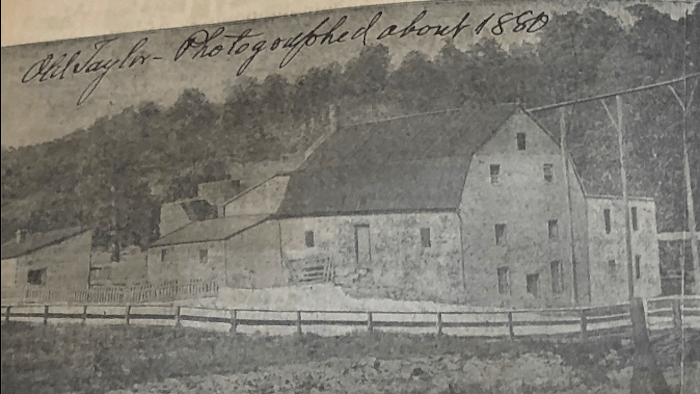

O.F.C. world’s most advanced distillery

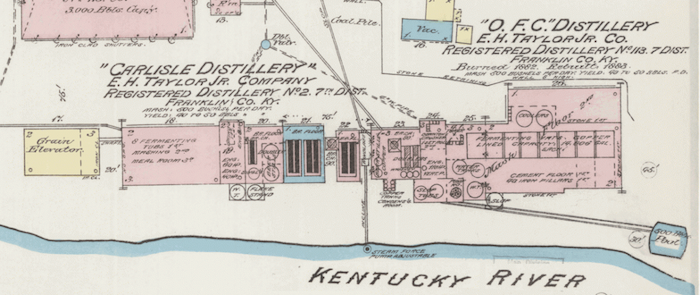

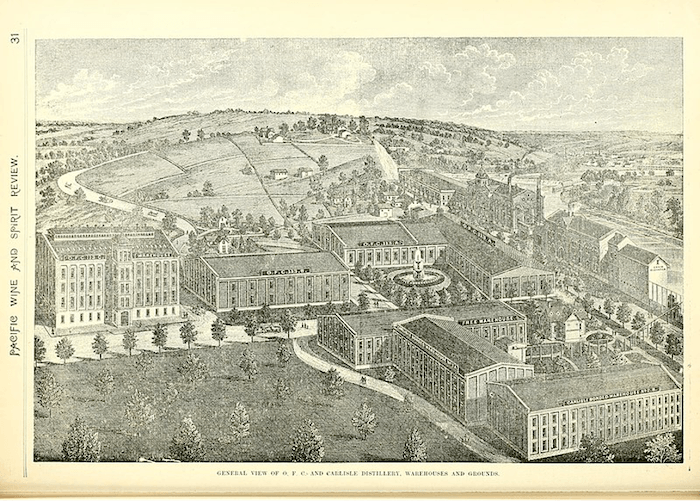

After buying the Old Swigert’s distillery in March 1870 for $6,000, Taylor upgraded much of the equipment into the renamed Old Fire Copper or O.F.C. distillery. In 1873, as the first modern-era Great Depression started, he demolished the old Swigert 3-storey stone building and converted it into the modern brick O.F.C. distillery with Stagg’s money. The new modernized $70,000 distillery held five hundred wooden mash tubs on the floor above the fermenters and distilling plant. He installed one of Kentucky’s first two all-copper beer column stills and a set of copper doublers in a separate room. The 500-bushels a day distillery had warehousing for 35,500 barrels. By 1874, Taylor’s O.F.C. 2-year-old whiskey was selling to Louisville and Cincinnati dealers for $2.60 a gallon. The business prospered until the Financial Panic of 1877, when whiskey withdrawals slowed, and consumption declined.

Long depression, Taylor confronts bankruptcy

The 1873 Financial Panic led to the Long Depression, causing whiskey prices to fall, especially in the premium segment, exposing Taylor’s business to bankruptcy by creditors in May 1877. Between 1877 to 1878 U.S. spirit withdrawals for consumption declined to 51,930,941 proof gallons (-14%), and Government tax revenue fell to $50,420,818 (-12%). Within weeks of buying James Pepper’s equity in the Old Pepper distillery, Taylor was forced to flee Frankfort after a June creditors meeting in Louisville declared E. H. Taylor, Jr. owed $446,654. Due to his euphemistically coined ’pecuniary troubles’, he probably left Frankfort to secure new lines of credit, leaving his son Jacob to reassure creditors he would honor his debts, which he did. His largest creditors were his partners in the O.F.C. distillery, Gregory, Stagg & Company, owed $150,000. Amongst Taylor’s more than a dozen creditors, James Graham was owed $8,000. George Stagg organized to pay the other creditors 20 cents in the dollar and gained control of the business at a heavily discounted value by December.

In January 1878, Gregory, Stagg & Company of St Louis offered Taylor a single share in his old Company, leasing Taylor the O.F.C. and Carlisle distilleries to oversee continuing production. Taylor was also forced to sell the Old Oscar Pepper distillery to George Stagg, who promptly sold it in May 1878 to James Graham for the $8,000 he was owed. In October 1879, Stagg’s firm formed E. H. Taylor, Jr., Company (not Distiller), rescued the O.F.C. distillery from collapse and supplied the working capital for the newly completed Arlington distillery to start production. George Stagg held the majority of the firm’s shares, appointing himself president, Taylor, the titular vice-president. Taylor’s reputation in the trade had pulling-power with national dealers who knew his whiskey as ‘O.F.C. Taylor’, ‘Fine Old Kentucky Taylor’, or simply ‘Taylor’s whiskey’. Since the 1870s, Taylor had been prominent in advertising and trade circulars to every whiskey dealer in the U.S., building his and his whisky’s reputation. Stagg needed Taylor’s imprimatur in the Company and on the whiskey to ensure continuing orders.

The high-standing of Taylor’s ‘liquid velvet’ was vindicated in 1880 when Taylor’s O.F.C. whiskey was assayed and selected as the official supplier of medicinal whiskey by the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army for hospital use, the first sour mash brand to be granted Spiritus Frumenti status. The U.S. Pharmacopoeia in 1863 rendered Spiritus Frumenti the first definition for whisky (sic): ‘Spirit distilled from fermented grain by distillation, containing forty-eight to fifty-six per cent of absolute alcohol. Whisky for medicinal use should be free of disagreeable odour and not less than two years old.’

Before Taylor lost all his distilleries by 1884, he built, rebuilt and invested in half a dozen distilleries after buying the Old Swigert distillery. His state-of-the-art O.F.C. distillery was the first he rebuilt after Mother Nature dealt it a fatal blow.

O.F.C. conflagration

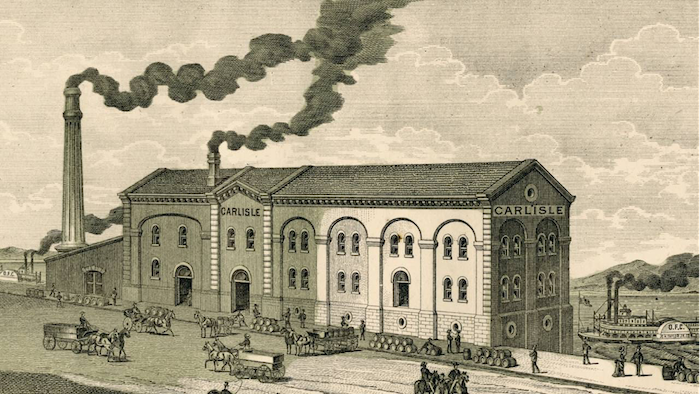

A lightning strike during a violent storm in mid-June 1882 destroyed the O.F.C. distillery requiring a complete rebuild. Taylor took the opportunity to modernize apparatuses with the latest improvements using the payout from the $20,000 insurance claim and investing an additional $24,763 to make it the world’s most technically advanced distillery. Taylor‘s new inventions were incorporated to improve the quality of the whiskey, such as his September 1881 patent for ‘pulverizing grape sugar’ by mechanically emulsifying maltose, glucose and dextrin to potentiate the fermentable yield. The new distillery, continuing to apply the precepts of the Crow plan, was back in operation by early 1883.

Taylor’s architectural design for the 1873 and 1883 O.F.C distillery replicated his work at the Hermitage distillery, adapting the Rundbogenstil-industrial style accommodating complete production, from grain to finished goods, under one roof. Each floor and the brick-walled rooms were discreetly partitioned for safety, cleanliness and operational efficiencies.

Kentucky harvested 50 million bushels of corn in 1870, giving Taylor an abundance of local grain, especially his preferred yellow flint crosses. Virginian settlers introduced old gourd seed crosses, and the red cob white dents were also popular with local distillers. As whiskey production escalated after the Civil War, local rye cultivation was supplemented by interstate volumes, and increasingly rye was imported from Canada on the new rail network. After 1874, Taylor contracted his malted barley supplies from the Kentucky Malt House in Louisville. They secured good quality new malting barley from California – by 1870, California was America’s largest barley cultivator exporting 8,783,490 bushels.

Grain costs varied by year, time of year, grade or specification. By the early 1870s, the distillery obtained Kentucky yellow dent corn crosses for 55 cents per bushel, winter red rye for around $1.00 and $2.00 for malted barley (English Chevalier and new malting varieties). Distillers faced the tension of grain cost variability and grade, ‘the mash bill’ while maintaining the desired flavor profile for a high-grade straight whiskey to retain its franchise. On receipt of the grain, it was twice cleaned, stored in an elevator before being sent to hoppers to be weighed and allotted for milling by cereal type.

Instead of millstones that pulverised some grain, two sets of corrugated steel rollers, a recent invention developed in Hungary, milled each cereal in the mash bill to a uniform meal or grist specification before mashing.

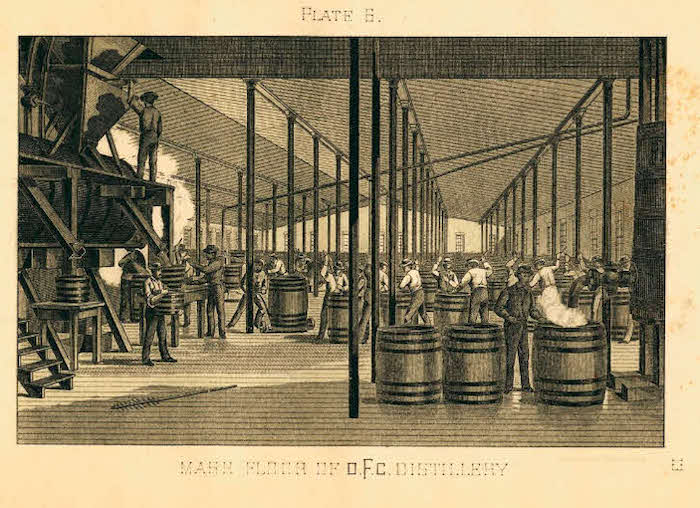

The distillery continued to hand-mash a bushel of grain per tub using spent sour mash distillers wash from the singling run on the large second floor covering 10,000 square feet, hundreds of tubs lined up for mashing. The corn mash was cooked at 112F, hand stirred, then pristine spring water added from a cistern to cool the slurry before adding the rye meal and malted barley to 70F. The latest globe ventilators removed mash vapors and the large arched windows supplied natural light. After stirring the mash, it rested 24 hours, sometimes up to 48 hours, determined by external conditions.

Rye and malt were added and stirred, so the enzymes achieved the desired level of diastatic conversion. The mash then passed through a crusher to ensure the yeast unimpeded contact to the mashed-out wash, then conveyed by copper pipes, to the floor below, into fourteen-copper-lined fermentation tanks, made of limestone blocks and sealed in English Portland cement holding 14,800-gallons. The copper was deemed to protect the flavor and was easier to clean than the traditional unsanitary wooden oak vats.

No fresh yeast was added, “whatsoever”, and left to open-ferment for at least 96-hours. Taylor followed the Crow plan that avoided the risk of yeast mutagenesis, preventing the precipitating of new esters and new compounds affecting the flavor profile. It also minimized microflora contamination than pitching fresh yeast, less hygienic in the 19th century, propagated from ‘mother’ dona jugs, thus safeguarding flavor consistency with each successive sour mash batch. The setback and barm used in his sour mash method was carefully monitored to avoid an exhaustive fermentation, ensuring some residual sugars were left to enhance the spirit’s flavor profile during distillation and maturation. As the beer was pumped to the stills, it was filtered to remove meal particles to prevent scalding.

The residuum of the strained meal was collected as stillage to fatten a herd of two hundred cattle. The stills were run low and slow Crow style, with a gentle, regulating heat for separately running the singling and doubling stills. During beer distillation, a customized cap engineered on the still head intercepted noxiously rank fusel alcohols. His ‘strain slops process’ and other manufacturing innovations formed part of Taylor’s patented process claimed to improve the flavor and yield by half a gallon per bushel. Taylor incorporated the Frankfort Whisky Process Company in 1874, holding 50% of the shares to market this proprietary method. The novel mash-ferment process was licensed to other American distilleries, even distilleries in the ‘High Wines Trust’. Clients included the Shufeld distillery, Manhattan Distillery, Vacuum Mashing Company in Peoria, Illinois, part of the Distillers’ & Cattle Feeders’ Trust, where he charged a royalty of 0.01¼ cent per bushel.

Further clues to Taylor’s whiskey innovations are revealed by his manufacturing inventions and proprietary processes that yielded superior whiskey. The fermented beer passed through a copper heater to another Taylor invention. An airtight, vacuum vessel of ‘peculiar interior construction’ was placed between the floors to ensure a uniform temperature before charging the singling beer stills. The singling stills were mounted over a wood-fuelled, direct fire furnace. Each charge was 150 bushels and distilled over ten hours. The spent distillers wash from the singling run was strained and pumped to the newly prepared mash tubs to cook a future cornmeal batch. A tall vertical lyne pipe sent the distilled spirit vapor to the condensing room where Taylor erected copper columns with a vapor chamber inside, made of converging walls, with cold water continuously running down to liquefy the gaseous distillate.

This engineering was one of the precursors to the modern shell and tube condenser that replaced the traditional serpentine worm inside a wooden tub or larger flake stand. William Grimble of London patented Britain’s first tube condenser in May 1825, but distilleries did not adopt it for another fifty years. After being led to the singling receiver, the low wines were sent to the copper doublers. These pot stills were of a swat shape with a reflux bowl and a vague description of a prototype-like dephlegmator attached.

The high wines vapor was sent to an atomizing column where a detersive process oxidized residual amyl alcohol and removed salts such as copper acetate, another Taylor invention or modification as similar industrial patents were registered from 1882. The distillate at the Old Taylor distillery was collected into the spirits receiver at 120 Proof. Piped into the cistern room, the spirit was diluted with filtered and distilled water to a few degrees’ over-proof for barrel filling. Local white oak was coopered into charred 42 to 45-gallon barrels; stave lengths were four inches shorter and of more depth than the current specifications of the modern 53-gallon barrel standardized for transport and storage by the Interstate Commerce Commission in June 1943 for Wartime efficiencies.

As Kentucky forests fell to the axe, the demand for barrels grew, Wynard’s cooperage in Aurora, Indiana, became his leading supplier in the late 1870s. The barrels were racked onto ventilated three-tiered warehouses beside the distillery to prevent mustiness from any moisture rising from the valley floor and the contiguous waterflow of Glenn’s Creek. Steam-heated pipes ran through the warehouses to control the maturation temperatures inside the bond stores to hasten extraction during the colder months.

Changing definitions by the Government on low and high wines led to confusion as modes of distillation between traditional pot still methods. The different patented closed systems required the I.R.S. to adapt differing yields and outputs. The invention of American patent steam stills in the first half of the 19th century, notably the wooden and copper bourbon steam stills, forced the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to fashion a new definition for gauging, starting in the July 1866 Act, modified in the July 1868 Act. Because the patent steam still often ran the distillation in a closed system (wooden chambered singling to doubler), the whiskey (no regulations set any time requirement in wood) was classified as low wines or proof spirit.

When the low wines from the singling still were intercepted by a receiving cistern, by pot still distillation, called the ‘old practice’, the second distillation in the doubler was also classified as proof spirit or high wines. When the low wines were purified by further distillation (or by registered rectifier), they came under the classification of high wines, i.e., over 150 Proof or 75% A.B.V. If distilled to a higher, purer cologne-like proof on patent column stills (over 180 Proof or 90% A.B.V.), they were defined as alcohol. The variety of stills construction and modes of distillation (grain, fruit, rum), classes of distilleries (and rectifiers) generated significant variation in the alcoholic yields, which made revenue accountability and the prevention of fraud more complex in computation and reporting for Treasury gaugers. By 1900, the Internal Revenue Gauger’s Manual ran to 623 pages of regulations, instructions and tables, from 163 pages in 1868.

New Arlington twin distillery becomes the Carlisle

By the late 1870s, demand for O.F.C. whiskey swelled with the bullish American economy. Plans for a second distillery were on Taylor’s drawing board in 1877, before his financial calamity cooled the economy. The E. H. Taylor, Jr, Company, majority-owned by Stagg, stumped up the investment to construct a similar scale distillery adjoining the O.F.C. The 500-bushel-a-day Arlington distillery started production in early 1880 to manufacture ‘standard sour mash all-copper whiskey’.

In March 1880, the country’s largest order of sour mash whiskey, 500 barrels of Arlington sour mash, was made by their Company agent in Memphis, Tennessee, to the wholesaler A. Vaccaro & Company. Because the distillery did not use small wooden tubs manually stirred by workers, it was not hand-made whiskey. Instead, steam-driven mechanical stirrers circulated the mash in large metal tanks, hence the term ‘standard sour mash’.

The Arlington was renamed the Carlisle distillery two months later after the Kentucky politician and Taylor’s colleague, John Griffin Carlisle. In May 1880, John Carlisle, known as the Bourbon Democrat, successfully moved a landmark statute in the U.S. Congress for the whiskey industry. The Carlisle Allowance Table extended the bond period to three years and made allowances for storage outages. The distillery renaming was in tribute to John Carlisle’s effective stewardship in the passage of the Act. Later as U.S. Senator, Carlisle introduced the August 1894 Carlisle Act extending the bond period to eight years. In March 1897, as a U.S Senator for Kentucky, he helped usher in the Bottled in Bond Act – legislation authenticating and guaranteeing straight whiskey thirteen years before national product identity standards for production and labelling. Supported by Carlisle, Taylor’s lobbying argued for the special status of straight whiskeys in the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act drafted by Dr Harvey Wiley.

Failing to achieve this objective, Edmund, and his son Edmund Watson Taylor, aided by Carlisle, now Secretary of the Treasury made persuasive representations to President William Taft during 1909. A consequence of these representations incited Taft’s landmark ruling, ‘What is Whiskey Decision’ in December 1909. This edict defined the product identity for straight whiskey by its modes of production and labelling standards. When serving on the Ohio Circuit in Cincinnati, President Taft’s father, Judge Alphonso Taft, presided over the world’s first case on whiskey standards brought by the Japanese Government in 1869. They alleged a Cincinnati wholesaler supplied ‘pure rye whiskey’, which Japanese chemists determined was adulterated with rectified grain spirits (high wines).

Judge Taft found in favour of the plaintiff, making the judgment that the whiskey, in this case, was not ‘pure whiskey’. The term straight whiskey had not entered the vernacular by 1869, but ‘pure rye’ made exclusively from malted rye and unmalted rye was in common usage before the 1860s. His son reached a similar decision for American whiskey consumers on straight versus blended whiskey fifty years later.

Spring Creek distillery venture

Before the O.F.C. distillery was rebuilt in 1873, the output from the original 1870 O.F.C. distillery was limited. To supplement his whiskey supply, Taylor encouraged Lewis Castleman, a Frankfort colleague, to partner in another small distillery. They built the Spring Creek distillery, also known as the Glen (sic) Springs distillery in August 1871 on Glenn’s Creek, where the old Shiel mill stood. Castleman separately owned the Daniel Boone distillery outside Frankfort, but it was not a sour mash distillery to the Crow plan. A year later, the pair fell out when Taylor reneged on buying $7,000 worth of the first year’s whiskey stock, as initially agreed. Court proceedings indicated Taylor suffered cash flow problems in 1872. Financial relief was delivered when Gregory, Stagg & Company injected fresh capital into the business in late 1872, too late for the Taylor- Castleman partnership to be salvaged.

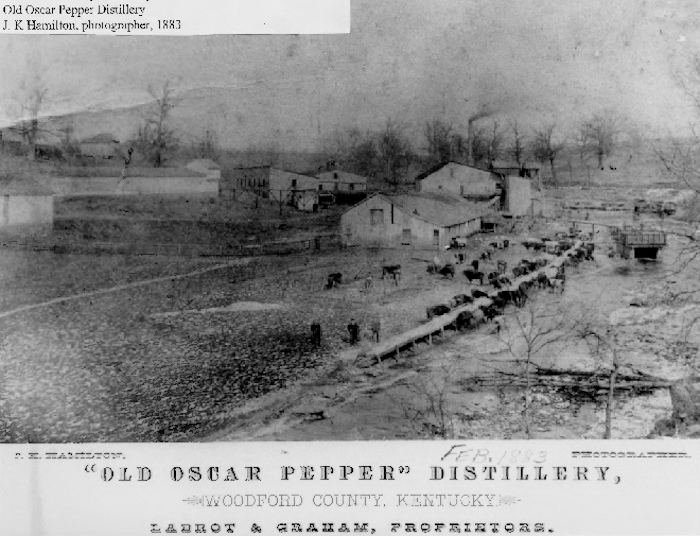

Oscar Pepper distillery redux

Flush with Gregory, Stagg & Company’s new funds, Taylor, constantly watchful to incorporate distilleries of the Crow plan into his whiskey empire, formed a new partnership with Oscar Pepper’s son, James Edward Pepper, in 1872. Teaching young Pepper, whom Taylor was once legal guardian, the whiskey business from ‘cornfield to high table.’ After a fire in 1873 destroyed part of the distillery and some of the barrel stock, Taylor invested $25,000 in 1874 to refurbish the Oscar Pepper distillery. The old pot stills also needed replacement as the copper walls were thinning to near-obsolesce, corroded by acidic sour mashes and sulphides after many years of usage.

Holding the majority of the shares in 1874, Taylor added the prefix ‘Old’ to the Oscar Pepper distillery, a word liberally used by distillers to create the impression a distillery and whiskey had heritage. Taylor’s distilleries and whiskey were bona fide ‘old’ compared with most competitors, where two or more years of aging qualified as old whiskey. Taylor moved William Mitchell back to the Old Oscar Pepper distillery from the O.F.C. distillery to head operations when it had completed its renovation and equipment refabrication. Mitchell began his distilling apprenticeship at the Oscar Pepper distillery under James Crow in 1848, taking the Crow plan and methods to other sour mash distilleries in the district. Taylor’s relationship with the Pepper family and the Oscar Pepper distillery began before Gaines, Berry & Company leased the Oscar Pepper distillery in 1867 as an executor to Oscar Pepper’s estate upon Pepper’s death in June 1865. Taylor was also involved in organizing a loan to Oscar Pepper in 1856 at Taylor, Shelby & Company.

Previously, when his uncle was the cashier at the Frankfort’s Bank of Kentucky, he likely loaned Oscar Pepper the money in 1838 to upgrade his distillery to the Crow plan from a one-bushel a day to a 25-bushel capacity in 1840. Edmund Taylor, an acquaintance of Oscar Pepper, would have known Glenn’s Creek’s preeminent resident, James Crow through his business dealings with Pepper and the community. The Taylor family’s relationship with Crow went back to his grandfather Richard Taylor, who sold Crow a sack of salt in 1829 after he arrived in the bluegrass region. Years later, in September 1869, James Edward Pepper, Oscar’s nineteen-year-old son, had the Court appoint Taylor his legal guardian; under U.S. law, he was a minor until 21. In May 1877, James Pepper faced insolvency; Taylor again stepped in and acquired Pepper’s remaining equity to help bail him out from his creditor’s debts.

Taylor’s ownership of the Old Oscar Pepper distillery was short-lived, as he too fell victim to mounting debts and sold the distillery to George Stagg a few months later.

Swigert Taylor distillery

After losing the E. H. Taylor, Jr., Company and O.F.C. distillery to Stagg, Taylor formed a separate company with his eldest son Jacob Swigert Taylor and purchased another sour mash distillery on Glenn’s Creek in 1879. They acquired the Anderson Johnson (& Yancey) distillery, the same distillery Taylor leased when he was a partner at Gaines, Berry & Company, where Old Crow whiskey was made between 1867 and 1869. Taylor renamed it the J. Swigert Taylor distillery, also known as the J. S. Taylor distillery, as E. H. Taylor Jr. Company was the property of Stagg. It was incorporated in Kentucky as a separate business entity to the E. H. Taylor Jr., Distiller. Jacob Swigert Taylor was christened after Edmund’s long-time friend, Jacob Swigert, whose brother Daniel Swigert built the original Swigert Old still house.

The J. Swigert Taylor distillery was a three-storey stone construction, with a 40-bushels a day capacity. The distillery was purchased from James (Jack) Johnson, Anderson’s son; it was one of the dozen distilleries in Kentucky working to the Crow plan. James Crow worked at this distillery in the late 1830s and was working there again in April 1856 when he died while attending the still house. The distillery produced 1,200 barrels a season, mashing one bushel per tub, charging the still with five bushel runs. John William Johnson, another son of Anderson Johnson, continued as the head distiller when the Taylor’s bought the business. Johnson initially trained in the Crow methods at the Oscar Pepper distillery from 1856 under his cousin, William Mitchell.

When Gaines, Berry & Company transferred Mitchell to run Anderson Johnson distillery, John Johnson took over as head distiller at the Oscar Pepper distillery from 1867 to 1869. Johnson returned to the family distillery when the Gaines, Berry & Company lease expired in late 1869. Taylor’s relationship with John Johnson later degenerated into an acrimonious Court case which Taylor won on appeal. The bitterness of their vexatious relationship began when Old Taylor distillery was sent into an assignment in 1893, and its affairs wound up. One of the members of the assignees, Security Trust and Safety Vault Company, lent Taylor money in 1894 (through Edmund’s wife, Fannie) to start a bottling business under E. H. Taylor Jr., & Sons Incorporated.

The purpose was to keep the whiskey and brand trading. Johnson would later allege he held eleven of the twenty shares issued in this new company. In 1897, Johnson was dismissed from the distillery, with the share dispute festering until he took legal action ten years later against the new Company of E. H. Taylor Jr., & Sons, Distillers. Johnson lost the case in January 1907, and no evidence was presented to Court that the transaction took place; he died two years later.

Taylor’s financial crisis in 1877 led to Stagg taking almost complete ownership of his business in 1878. However, Taylor needed more money to discharge his remaining debts forcing him to sell the J. Swigert Taylor distillery to Stagg by October 1882. Taylor repurchased the J. Swigert Taylor distillery six years later when Stagg sought to remove Taylor entirely from the business. Taylor’s liquidated his single share, and as part of the exit agreement, Stagg sold him the J. Swigert distillery in November 1886. Taylor, now debt-free, was able to raise a loan from Stagg’s partner, James Gregory, to repurchase the distillery in December.

The distillery was razed in January 1877 and replaced with the new state-of-the-art Old Taylor distillery. Reflecting later on his misfortunes over the previous ten years to a Frankfort journalist, Taylor remarked, “Sales stopped, money became tight before I knew it, interest exceeded earning.”

Newmarket distillery

In 1885, during his tumultuous insolvency period and estrangement with George Stagg, Edmund Taylor and his sons Jacob and Kenner purchased equity in the Old McBrayer distillery on Hinkston Creek, Mount Sterling in Montgomery County. John H. McBrayer built the distillery in 1870. As well as Taylor and his sons, the investment syndicate included L.C. Norman and John Meagher, president of Frankfort National Bank, remaining secretary and treasurer of the distillery until the late 1890s. The Old McBrayer distillery had several owners in the 1880s, including John’s second-cousin William Henry McBrayer of Cedar Brook distillery in Anderson County near Lawrenceburg, and later Willis Johnson of Cincinnati bought the distillery in the early 1880s. Johnson sold stock in the company to the Taylor syndicate a couple of years after purchasing it. Whereupon Edmund Taylor upgraded the distilling plant and renamed it the Newmarket distillery.

It started production in March 1887, the same month the Old Taylor restarted production under E. H. Taylor Jr., & Sons. Unlike his other distilleries, Newmarket was a sour mash, but not entirely to the Crow plan, although it appears Taylor may have attempted to bring it in line with hand mashing and copper equipment. The distillery produced 2,000 barrels a year. Taylor and his Frankfort partners sold most of the shares in the distillery back to Willis Johnson in 1888, with Taylor remaining president until about 1892, to assist in marketing his Newmarket whiskey, along with his Old Taylor and J. S. Taylor whiskey. Much of the Newmarket production, along with allocations of Old Taylor barrels, was sent to Bremen and Hamburg through the Export Storage Company for ‘unlimited bonded period’ and tax minimization.

Distilleries lost

In 1886, as Taylor and Stagg’s relationship deteriorated, a decision was made to remove Taylor from the business entirely, with George Stagg liquidating Taylor’s single share in the Company. As part of the exit agreement, Stagg struck a deal for Taylor to buy back his J. Swigert Taylor distillery and 1,200 barrels. Stagg’s terms were for Taylor to ‘relinquish all interest in and to the effects and business of the company, and retire therefrom’. Clay Gregory, Stagg’s business partner and son of James Clay, one of Stagg’s original partners, loaned Taylor the money to rebuild the J. Swigert distillery, alleged $10,000. Disagreements with Stagg continued after Taylor departed from the E. H. Taylor, Jr. Company, as Stagg continued to use Taylor’s name and signature. In October 1889, Taylor’s injunction prevented George Stagg & Company from using Taylor’s name and signature on O.F.C. and Carlisle whiskeys. In November 1887, Stagg registered the George T. Stagg Company as the O.F.C and Carlisle distilleries owner but continued using Taylor’s name and signature on the labels.

The decision was appealed by George T. Stagg & Company, and in 1894 the Courts found in Taylor’s favor again, awarding him $50,000 in damages and the profits from 2,200 whiskey barrels. George Thomas Stagg retired in 1890, his stock in the company controlled by Duffy and other investors, in ill-health he died May 1893. The litigious directors of the George T. Stagg Company, which included President Walter Duffy, continued to use the Courts and Taylor’s signature until the final judgement in June 1902 prohibited its use.

Preamble to the golden years

With his sons Jacob Swigert, Edmund Watson and Kenner, Taylor demolished the J. Swigert distillery and built the new Old Taylor distillery in early 1887. Edmund Taylor formed E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons on January 1st, 1887, the day after departing from his previous E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Company, Distillers, owned by George Stagg and partners. With Gregory’s money, Taylor could reclaim the J. Swigert distillery and stocks of bonded whiskey to start bottling Old Taylor whiskey.

Edmund H. Taylor Jr.’s reputation as America’s most outstanding whiskey proprietor, respected politician and servicer of debts held him in good stead. Kentucky banks loaned him the money to build his dream distillery to manufacture whiskey that rivalled; some said surpassed James Crow’s whiskey. The Old Taylor distillery and whiskey cemented his reputation as distiller without peer.

Distillery coda

Spring Creek distillery, Glenn’s Creek: Rebuilt in 1881 by Louisville distillery investors Greenbaum, Stege and Reilly, they increased production of sour mash whiskey to 170 bushels a day. The Glen (sic) Springs Distilling Company was registered under Christian Stege as the primary distiller and operated until 1899, when the Kentucky Distillers and Warehouse Company bought the distillery. Julian Kessler formed Kentucky Distillers and Warehouse Company in February 1899 to control Kentucky whiskey production acquiring 90% of standard bourbon whiskey brands and 57 distilleries in the Commonwealth by the early 1900s. Distilling ceased at the distillery in 1900, and the plant was removed; however, the site continued its registration for warehouse stock until Prohibition. In 2015, the remnants of the distillery buildings opened as a bed & bedfast, The Ruin.

Newmarket distillery, Mount Sterling: Under Willis Johnson’s proprietorship, the distillery traded as Old McBrayer Distilling Company, J.H. McBrayer Distilling Company and New Market Distilling Company. Johnson sold the distillery to Kentucky Distillers and Warehouse Company which became part of National Distillers Product. The distillery closed before Prohibition, and the distillery partially dismantled. In 1937, the distillery rebuilt as McBrayer Springs Distillery Inc. with Frank Gorman as president. The enterprise only lasted several years before the distillery was razed. National Distillers owned the brand name and continued to sell Old McBrayer whiskey, using stock from their other Kentucky distilleries for several decades, presumably whiskey from the revamped Old Taylor distillery.