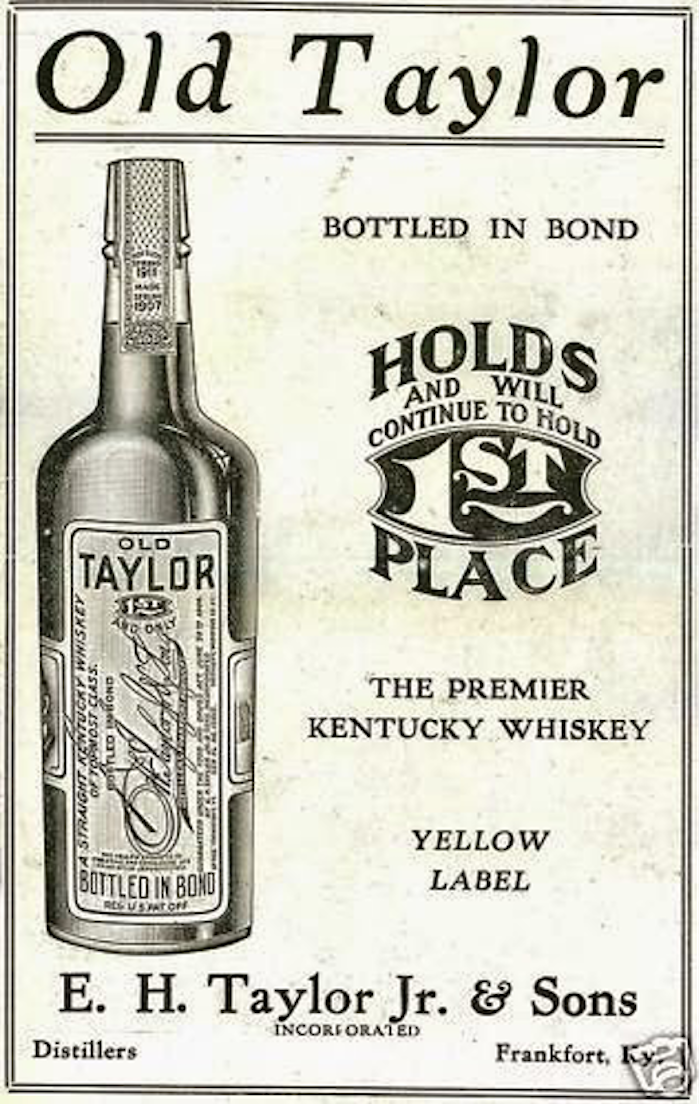

In Part 1 we explored the the beginnings of the topmost period of legendary American distiller Edmund Taylor. Jr;s whiskey making days. After Taylor and his sons repurchased the Old Taylor distillery from Security Trust & Safety Vault Company in 1895, they entered their golden years. The Old Taylor brand became synonymous with the Government guaranteed ‘topmost’ whiskey after the Bottled in Bond Act passed in March 1897. In 1912, Taylor’s Bottled in Bond achieved market leadership in whiskey’s premium or luxury class. Since the distillery opened, a small band of workers and their families began populating the village of Taylorton.

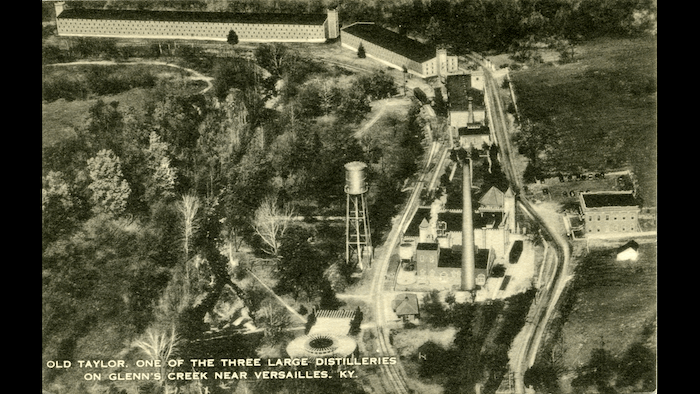

The flourishing of the Taylorton community was a reflection of the distillery’s increasing prosperity. The distillery’s extensive gardens bloomed, and parklands rose along the lush landscape around the Glenn’s Creek hillside. The distillery’s modern facilities continued to expand to twenty-one buildings, adding warehousing, a railway station and visitor amenities to meet increasing demand. Old Taylor thrived over the next two decades, and its whiskey became America’s most celebrated brand epitomizing exceptional quality.

The theatre of distilling

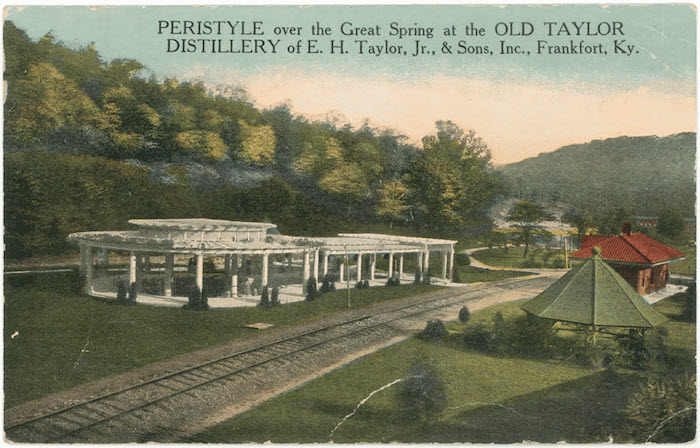

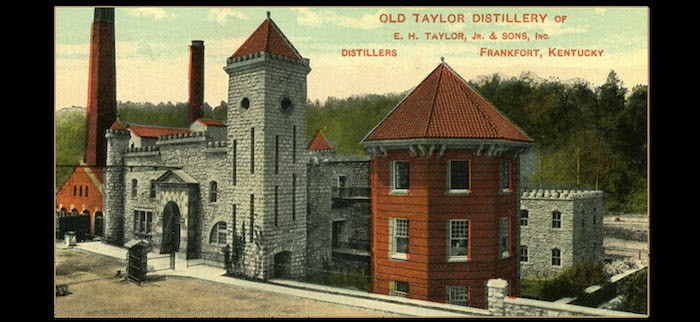

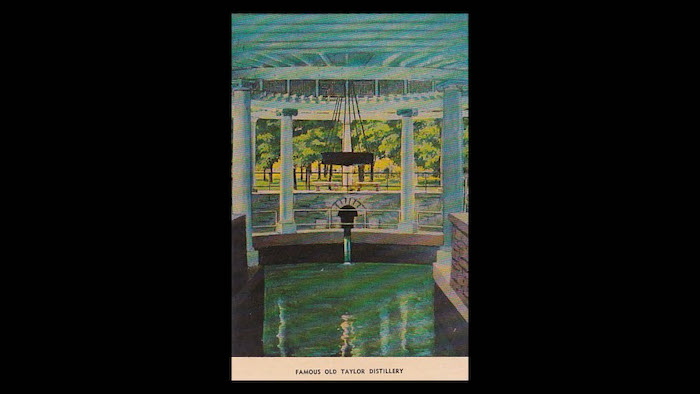

Taylorton’s centerpiece was the striking Old Taylor still house built as a medieval-styled castle from local river limestone with a façade of crenelated battlement walls and corner turrets. Taylor’s castle was a striking symbol of the grandeur and authority his whiskey commanded. As a local wag remarked about the imposing edifice, “Taylor now is the king of Kentucky whiskey.” The nearby ‘great spring’ water source was surrounded by a Roman-like peristyle colonnade enclosing the 14,000-gallon pool in the shape of a key, a visual metaphor to ‘water being the key to the whiskey’. The inner bluegrass region possessed unique geology due to the karst limestone draining into the Kentucky River basin. Rising in this Ordovician limestone stratum is the 300-foot-deep Lexington formation embedded with other limestone layers, whose hydrology is ideal for fermentation and whiskey making.

Glenn’s Creek was prized as this ancient limestone outcrop consisting of calcite ‘birds-eye limestone’. Embedded in the Lexington limestone are matrixes of collophane (cryptocrystalline apatite) and calcite. These mineral nutrients dissolved in water and issued from abundant spring water sources promoted vigorous yeast reproduction and healthy zymological activity. Four hundred and eighty million years of the earth’s plate tectonics and sedimentary accumulation from ancient seas made the inner bluegrass region a unique geological zone for whiskey-making and livestock breeding.

The landscaped grounds surrounding the distillery were another European import. The Bavarian Decree of 1812 instituted the introduction of the biergarten at large breweries in southern Germany, allowing families to bring food for picnics, play games, participate in community sing-alongs and drink the brewery’s beer. These new, large breweries stored their lager in underground cellars; overhead, they planted linden and chestnut trees to keep the beer kegs cool, furnishing a shaded canopy for the public to mingle beneath. By the 1850s, German immigrants to North America constructed large lager breweries in the same industrial Rundbogenstil-style to attract custom to their American lager beer gardens. American breweries added amusements to entertain families with skittles, bowling alleys, concert halls, restaurants, museums, rifle galleries and fishing ponds while dispensing beer to the patrons. These were forerunners to amusements parks and family entertainment destinations such as Coney Island and Atlantic City in the latter half of the 19th century; later, Walt Disney translated his celluloid characters and movie genres into the well-known theme parks.

The façade of Rundbogenstil architecture concealed powerful steam engines with industrial-scale brewing equipment for the new era of mass-production. Britain, and Australia and other Anglo countries borrowed this architectural style for breweries and industrial buildings. Taylor borrowed the Rundbogenstil round-arch style, incorporating it into the Hermitage, O.F.C. and Carlisle distilleries. To heighten the aesthetic and amusement features at the Old Taylor distillery, he took a radically different architectural direction, erecting the ‘splendid’ Medieval-style castle masquerading as a distillery. The practical and streamlined warehouses used only natural light for fire safety, holding 40,000 barrels. Described to the visitors by the guides as ‘miles of barrels’, it formed part of the tour explanation of the exacting and unique methods used in the manufacture of Old Taylor whiskey.

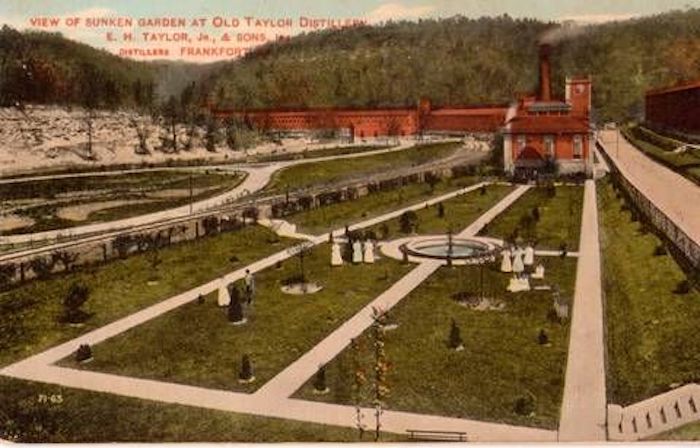

Taylor had the scenic 82-acre campus landscaped to make the distillery grounds a ‘delightful’ pleasure garden for visitors to enjoy nature and promenade. A large B.B.Q. pit dugout and a burgoo house with ninety-two kettles, served Kentucky stew with cornbread to feed the visiting multitudes. He entertained male guests with bands, juleps, cigars and cockfights in his custom-built cock house. He erected ‘artistic houses’ surmounted by red-tiled roofs with roses trailing up over the supporting arches at places where natural springs egressed. Large basins made from limestone rock channelled water into storage cisterns. Vines planted by walls grew into verdant shawls, softening the bright limestone. He filled the property with enchanting gardens and displays featuring a giant sundial, a sunken English rose garden, stone bridges, gazebos, and a pergola with a reflecting pool.

Walking trails bordered by flower beds led sightseers along sealed footpaths to safely carry foot traffic where they ‘never soiled shoes.’ He employed Kentucky’s leading horticulturist to design gardens of azaleas and hydrangeas and plant thousands of trees across the much-denuded landscape to create a bucolic parkland and whiskey wonderland in the heart of the bluegrass.

Kentucky’s many modes of production and classifications of whiskey

Taylor remarked only a dozen ‘hand-made sour-mash, all-copper fire’ distilleries operated in Kentucky in 1868; by 1892, less than half of these remained faithful to the principles of the Crow plan. Distilleries that produced whiskey to the Crow plan were all located around Woodford, Franklin, Fayette and Anderson Counties, where Crow’s sphere influence was firmly established in the manufacture of these high-grade whiskeys. Few distilleries could legitimately claim their whiskey as ‘hand-made’, where the mash was cooked manually, stirred by wooden oars in small tubs by hand, not in large tanks with mechanical stirrers rotated by a steam engine or draft livestock power.

Most Kentucky distilleries prepared their beer by sweet mash (fresh yeast) and distilled their beer in triple-chambered wooden steam stills. Until Prohibition, this remained the most popular still construction, known as the bourbon steam plan with a boiler, or American still, whether the beer was sweet or sour mash fermented. These steam stills boiled the beer in three vertical chambers or compartments, sending the singling vapors directly into a wooden or copper doubler before condensing the distillate through a copper worm submerged inside a wooden flake stand cooled by running water. These single run modes of distillation manufactured a spirit of inferior composition due to higher fusel oils and lower alcoholic strength, resulting in lower-grade whiskey, frequently rectified and adulterated to make a more palatable whiskey.

By employing a columnar still or by mounting a multi-chamber beer column atop a pot still base, the hybrid steam still purified the spirit proof at higher fractions, with the resultant overproof spirit called high wines; above 150 Proof or 75% ABV. This distillate was filled into unburnt barrels for industrial applications or for compounding into blended whiskeys.

In 1870, the Internal Revenue Service identified six modes of production in Kentucky with six whiskey classifications. The most cost-effective mode of distilling was the bourbon steam still generating greater volume throughputs at a significantly lower cost per gallon. Sour mash distillers using bourbon stills made whiskey at less than half the price of the Crow plan at Taylor’s O.F.C. and Old Taylor distilleries. Taylor accused this type of plan and plant as inferior, ‘filthy and sour whiskey’, and wooden stills he slammed as ‘barbarism’, especially the mountain pine-top stills cut from conifers. He denounced the quality as “carelessly made whiskeys, whose aim is quantity, and whose objective is mere chaffering for cheapness”, especially the product made by the ‘High Wine Trust’ that was generating 87% of America’s spirit production by 1890.

Taylor used the derogatory High Wines Trust term to describe the Distillers’ & Cattle Feeders’ Trust foundered in May 1887. Within three years, they controlled eighty-six large distilleries in half a dozen States. Their goal was to establish a cartel to control whiskey prices. However, the moment they seemed unassailable, the Government clipped their wings with the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in 1890, resulting in the Trust’s break-up.

Most of the whiskey distilled in Kentucky employed various modes of production to manufacture bourbon and rye whiskey of varying grades, much of it blended with high wines and compounded into a variety of whiskey flavor styles. Most of the Kentucky distillers used the sweet mash method. It was faster to ferment, 48 hours versus 96 hours, and employed less capital expense in the plant and fuel, thus making it more cost-effective to manufacture but inferior in flavor. Bought cheaply by trade and consumer, it dominated sales by wholesalers, retailers and private/contract labels. In 1892, in Mida’s Criterion, Taylor wrote that less than six distilleries in Kentucky produce hand-made, sour mash, all-copper whiskey; he alleged almost all Kentucky distilleries misleadingly labelled their whiskey ‘hand-made sour mash’.

In northern Kentucky’s 6th Distilling District, there were twenty-four distilleries opposite the rectifying city of Cincinnati. One distillery, Taylor identified as a ‘daisy name’ company, as they operated under sixty-four different firms, everyone passing off as a distillery, many claiming hand-made sour mash on their labels. Taylor may have been critical of the competitive quality of standard Kentucky bourbon; he became almost apoplectic about blenders and rectifiers ‘debourbonizing’ the industry with their ersatz-style whiskeys, he called ‘artificial’, ‘imitation’, ‘synthetic’ and ‘bogus’.

The industrial age for whiskey mass-production arrived by the 1880s. In 1883, a handful of distilleries in Peoria, Illinois, mashed 35,587 bushels a day, or 17.5 million gallons (25% U.S. production), to Kentucky’s 6 million gallons, of which 4 million was straight bourbon and rye. The term ’straight’ was a Kentucky trade term to differentiate their ‘honest’ bourbon-style whiskey from the very high or all corn mashes made on single distillation plans or the new continuous American beer stills. These new column stills were responsible for the high wines and rectified spirit made voluminously by the new industrial distilleries populating America’s sprawling corn belt.

The term ‘pure’ became the vernacular property of rye whiskey as many rye whiskey recipes were made from 100% rye/malt mash, similar to the Scottish pure malts made exclusively or purely from malted barley. By the 1890s, larger mid-western distilleries surpassed Peoria’s distilleries, with the Majestic distillery in Indiana mashing 12,000 bushels a day, and in Iowa, International distillery 6,000 bushels. Taylor castigated these pseudo-whiskeys with verbal jibes, “the stomach groans under the domination of a new ruler.” Most of their production went to industrial (heating, lighting) and arts use (varnish), with the balance for blending and compounding into lower-priced whiskey brands and the burgeoning patent medicine industry. This quack industry was brought to commercial life by the 1862 Revenue Act when excise tax was sharply reduced on medical tonics containing alcohol.

The importance of the re-import trade

Kentucky’s hand-made, sour mash, copper-fired whiskey brands were not only the most esteemed whiskeys; they enjoyed high demand, even at top-shelf prices: Old Crow, Hermitage, J.S. Taylor, O.F.C., Old Oscar Pepper, Old McBrayer’s Cedar Brook and Old Taylor. Hand-made sour mash production volumes were constrained by the higher quality standards, slower production methods and lower-yielding gallon output per bushel. These distilleries ranked as smaller-scale manufacturers, mashing under 1,000 bushels a day, compared to the massive Ohio, Indiana and Illinois distilleries producing grain spirit on industrial scales. Taylor’s success spread beyond America. In the late 1870s, O.F.C. sour mash and quantities of Hermitage and Old Crow whiskey were exported to Europe, South America, and the Asia Pacific.

U.S. Treasury permitted exports from five ports: New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Orleans. Establishing sales in a foreign country, the distilling company or its export dealer needed to appoint a local agent to manage logistics and distribution costs through wholesalers and the different national jurisdictions through retail outlets permitted to sell and serve alcohol. Most exports were sold as allotments; few straight bourbon, pure rye and sour mash brands achieved sustained sales in overseas markets. E. H. Taylor Jr., & Sons, through their New York dealer, established sales in France with St Arnould & Company of Epernay France in October 1890. Like other European countries, the French were unfamiliar with the taste of American whiskey, preferring brandy, rum, absinthe, schnapps and other local spirits, marginalizing bourbon sales to grand hotels and expatriate communities.

The greater bulk returned to American shores as ‘re-imports’ and extra-aged whiskey in a financial manoeuvre to minimize excise duty. By 1870, the domestic demand for ‘fine whiskey’ in America grew, estimated at 13 million gallons per annum, or 16% of total spirits consumed. By comparison, in 2021, super-premium volumes are about 11% of the American spirit market. To defer tax payments and over-production years, distilleries and dealers sent barrel shipments of straight whiskey overseas for storage to minimize tax. Taylor and his agent sent consignments of barrels to Bermuda and Germany – over two-thirds of all exported American straight whiskey went to Hamburg and Bremen, primarily for storage and aging.

Between January 1883 and March 1890, 320,977 barrels of 46-gallon capacity were exported at the Government standard, with 75% shipped to Bremen for storage. Another event that benefited the domestic whiskey was the deferral of excise tax from two to three years in May 1880. In August 1894, the law was amended, extending tax-free bond to eight years; Taylor’s hand was behind these statutes. Aging premium whiskey in foreign ports was financially prudent until the series of more favourable U.S. bond laws and rising foreign tariffs and storage fees eroded any off-shore benefits.

The financial motivation to avoid putting fine whiskey into American bond stores started when excise duties rose from seventy cents per proof gallon to ninety cents in July 1875, incentivizing whiskey aging overseas and maximizing profits. Whereas imported spirits paid a flat $2.00 per gallon, raised to $2.50 in 1894, regardless of spirit’s years in a cask or when shipped at a higher proof for dilution at bottling or serving in bars. Exported whiskey could be aged for many years and only pay customs on the returning residual volumes, less outages. Savings were significant before 1894; a whiskey barrel boomeranged back from Europe for $7.15 after five years of storage. If warehoused in Kentucky after three years, it faced taxes and storage overheads of $26.06.

In 1880, the U.S. distilled 91.4 million gallons of spirits, of which 22.7 million was straight bourbon and rye. Most of the export spirits were high wines and rectified alcohol for industrial use and blending to make potable spirits. After phylloxera devastated Europe’s vineyards and brandy production began declining from the 1880s, American spirit blended into shrinking European brandy stocks as French, Spanish and German brandy and fortified wines. Ironically, the microscopic insect responsible for destroying Europe’s grapevines was imported on native American grape rootstock for experimental plantings in French vineyards during the late 1850s. As the U.S. Government extended bonding periods in 1894, it coincided with increases in European tariffs, higher insurance premiums and rising storage fees resulted in the export-reimport trade contracting and discontinuing by the late 1890s.

Since Lincoln’s Administration, proposals were expostulated to protect and enhance the product quality of whiskey’s manufacture and labelling under Government guarantee. In 1893, the Judiciary Committee developed a bottled in bond stamp as the first Government attempt at a certification system prepared by Treasury submission. Through Taylor and his sons’ lobbying of Government agencies, Congressional committees, and individual politicians such as U.S. Secretary of the Treasury John Carlisle, the bill eventually moved through the Ways & Means Committee to the House. When Congressional approval passed, President Grover Cleveland signed the Bottled in Bond Act into law on March 3rd, 1897, on the last day of his administration.

No sooner had Taylor received the green tax stamps from the Government printer to adhere over the corked bottles, he secured an order of 10,000 cases of Bottled in Bond from his Chicago agent in September 1897. Bottled in Bond proved increasingly popular with the public, and his label became the bestselling Bottled in Bond brand by 1912. Total Bottled in Bond depletions skyrocketed from 535,588 proof gallons in 1898 to 10,420,375 gallons in 1913. Kentucky represented 70% of all straight bonded whiskey withdrawals. Fifty distilleries in America were registered with the Government, accredited for Bottled in Bond sales.

By 1910, Taylor enjoyed financial and personal success. The December 1909 Taft Decision defined straight whiskey in law. Decades of litigation and appeals from numerous trademark infringements by competitors and disputes amongst disgruntled shareholders receded, many adjudicated in Taylors’ benefit. Taylor retired from politics in 1904 but remained active as president at his distillery with this three sons. He relished pastoral life breeding prize Hereford cattle and was lauded by newspapers for breeding ‘ the greatest herd of purebred, prize-winning Herefords in the world’. In November 1918, Taylor paid a record $17,300 for an English stud bull.

His philanthropic donations benefited the local community, and he enjoyed the bounties of a growing, prosperous family. In 1909, E. H. Taylor, Jr. Sons, generated over $1 million in revenue and $500,000 in annual tax to the Internal Revenue Service. During the distilling season from early October to early June, the distillery mashed 125,000 bushels of grain, fattened 700 head of cattle and filled over 10,000 barrels. The whiskey was aged at least five years and shipped 1.5 million cases, depleting 18 million bottles since September 1897. His whiskey was distributed through a national network of dealers to loyal consumers who willingly paid a premium for the whiskey without peer.

The business of entertainment

Taylor actively promoted his distillery as a regional destination attracting public sightseers and garnering national print media attention. The opening of the new Highland railway line along Glenn’s Creek in December 1907 had a spur line to Taylorton, the distillery’s new railway station. Built beside the spring peristyle, it connected the distillery to Frankfort and the Nashville & Louisville national rail network. Visitors and workers paid 30 cents a round trip, leaving Frankfort Monday to Saturday at 6 A.M., returning 5 P.M. By rail, road and boat, a continuous flow of visitors and raw materials arrived daily. They left as sated revellers and finished goods. Taylor invited influential people to visit and endorse his goods, including politicians, journalists, academics, company presidents and industrialists. He organized special events for communities and businesses to meet. On weekends B.B.Q.s and picnics attracted the first whiskey tourists to experience the distillery’s facilities.

Upon arriving, guests were escorted on a tour of the distillery and presented with one-tenth of a pint mini-bottle (47ml) of Old Taylor whiskey. In a highly competitive industry where thousands of brands clambered for attention, Old Taylor whiskey bottles needed to stand out, so he introduced the yellow label in January 1910; the paper manufacturer described the paper as ‘old gold’. When Old Taylor became the best-selling Bottled in Bond whiskey by 1912, he added ‘1st Topmost, supreme’ to the label and advertisements. The largest bottling order was November 1915, when 35,000 cases of Bottled in Bond were packed and shipped.

In grand hotel bars and restaurants where they served Old Taylor whiskey from the barrel, the cask had polished brass hoops and decorative barrel heads to catch the patron’s eye, from where bartenders filled elegant Old Taylor decanters to serve the whiskey. Old Taylor bar merchandising and advertising materials elegantly reiterated the brand identity and distinctive packaging as conspicuously as the Old Taylor distillery stood out from the Kentucky landscape.

Educating the public about his exacting methods made tourism an informative and entertaining way to showcase the effort and care taken to produce the world’s finest sour mash whiskey. Taylor’s experiential ideas heralded the dawn of whiskey tourism and the era of modern whiskey marketing. The next distillery to open up to day-trippers and regular public tours was Tennessee’s Jack Daniel’s Lynchburg distillery in the mid-1950s, opening a visitors’ center, Bethel House, at the distillery entrance in 1960. In Scotland, the first tours began in 1969 at the Glenfiddich distillery situated in the Speyside hills outside Dufftown. In Ireland, tours started in 1992 at the Old Midleton distillery in Cork.

Today, it is rare to find a distillery not open to the public or with a visitor’s center selling branded merchandise and whiskey, along with commemorative bottles and special releases. Since Old Taylor, no other distillery has invested in the total theatrical experience with such imaginative panache – from the majestic castle setting to landscaped gardens turning whiskey into a public spectacle and memorable impression for day-trippers. By abiding by the Crow plan principles in the manufacture of fine whiskey and adapting equipment advances and improved innovations in the process, Edmund H. Taylor Jr. was credited for producing the world’s finest whiskey. First at the O.F.C. and later at the Old Taylor distillery.

Taylor epilogue

In his later years, Taylor lived comfortably at Thistleton, his magnificent 1890 Queen Anne mansion built in 1891 on 900 acres outside Frankfort on the Louisville Road. Infected by influenza, Edmund Taylor Jr. died of pneumonia at 93 years of age in the afternoon of January 19th, 1923. After his death, his family subdivided Thistleton estate, selling the home and the original homestead lot of 160 acres to George Collins at auction for $73,735. Over the coming decades, the house fell into disrepair. It was demolished in the 1960s for property development, becoming the Thistleton Heights neighborhood. In circa 1900, Taylor bought a farm from Alex Wright outside Frankfort in Woodford County between Frankfort and Versailles. He renamed it Hereford Farm and slowly expanded the property to 3,000 acres. He turned Hereford Farm into America’s premier Hereford stud during his last decade. Hereford Farm hosted the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and, for his efforts, was awarded Honorary Master of Hospitality in April 1917.

Months after his death, the family subdivided the farm selling the main homestead to Richard Baker; his prize Hereford herd sold to Cunningham of Pennsylvania. Today, the farm is known as the famed horse farm, Ashford Stud, part of Coolmore, the world’s largest thoroughbred breeding operation. Ashford Stud is the home to recent triple crown winners, Justify in 2018, and American Pharaoh in 2015.

Distillery coda

O.F.C. distillery Leestown by Frankfort: Since 2011, Old Taylor whiskey has been manufactured and marketed by Sazerac Company at the Buffalo Trace Distillery, Frankfort, as ‘Colonel E. H. Taylor Small-Batch, Bottled in Bond, old fashioned sour mash whiskey.’ At the site of Taylor’s original O.F.C. Leestown distillery. Taylor’s O.F.C. distillery was renamed the George T. Stagg distillery in September 1904. In 1885, George Stagg leased the adjoining Carlisle distillery to Walter Duffy of the Rochester Distilling Company, New York, the patent medicine producer of Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey. The two Leestown distilleries soon formed part of Duffy’s New York & Kentucky Company, America’s third-largest distilling combine, formed after the original Whiskey Trust was broken up under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.

Duffy bought the Carlisle distillery in 1893, with business partner Henry Naylor of Eire Distilling Company Buffalo New York, took control of the George Stagg Distilling Company in 1895, owning the O.F.C. distillery. The Carlisle distillery was remodelled in 1895 to make high wines for patent medicine and renamed the Kentucky River Distillery in 1898. The 1906 Pure Food & Drug Act began the delegitimization of patent medicine, and in 1910, the distillery was leased to the Chicago firm of Einstein & Palfrey. The distillery closed in late 1917, with much of the Green River distillery premises and plant dismantled during Prohibition. With the advent of Prohibition, the New York company obtained a license to bottle and sell medicinal whiskey made at the George T. Stagg distillery. In the early 1920s, Naylor sold part of his equity in the George T. Stagg distillery to Albert Blanton’s A. B. Blanton Small Tub Distilling Company. Schenley Distillers Corporation invested in restarting the distillery in 1929, buying out Naylor when Blanton obtained a special distilling permit from the Government to replenish dwindling stocks of medicinal whiskey.

Production resumed in April 1930. In early 1933, Blanton sold his remaining shares in the George T. Stagg distillery to Schenley. After the repeal of Prohibition, the distillery was newly refitted to restart production at much higher volumes. Stagg was one of six Kentucky distilleries to resume distilling in 1934, releasing its first 4-year-old Schenley Ancient Age straight whiskey in 1939. Schenley continued to manufacture numerous bourbon and rye whiskeys from the Ancient Age distillery until they sold the Leestown facilities to Ferdie Falk and Bob Baranaskas’ Age International Inc. in December 1982. Two years after buying the distillery, the American whiskey industry descended into a three-decade-long decline. Production fell to around one million gallons by end-1975, from a peak of 14 million proof gallons in 1973.

In 1991, they sold a 22.5% stake in Age International Inc. to Takara Shuzo Company in Kyoto, a Japanese beverage conglomerate and the distributor of Ancient Age bourbon in Japan. A year later, Takara Shuzo bought out the equity balance of the Leestown Distilling Company and the brands held by Age International Inc. for $20 million, then promptly sold the (now named) Albert Blanton distillery to William Goldring of Sazerac in September 1992. The distillery was renamed Buffalo Trace distillery in June 1999 and today produces many of America’s most award-winning whiskeys, including W. L. Weller, Blanton’s Single Barrel, Sazerac Rye, Eagle Rare, Pappy Van Winkle range and E. H. Taylor Jr. Since Prohibition, the distilling plant has undergone significant and numerous equipment upgrades, modernization and expansion.

While no longer operating to the Crow plan, it continues to apply some of the Crow and Taylor principles, manufacturing the high-quality sour-mash bourbon and straight rye whiskeys. Significant technological advances during the past century were incorporated into the Leestown plant, such as modern pressure cookers, to distilling the beer on the massive 84-inch-wide continuous copper column beer still. Crow and Taylor’s tension of applying modern innovation with old, proven methods continues the quest to find bourbon’s elusive holy grail. The legacy of James Crow’s plan at the Old Swigert distillery, modernized by Edmund Taylor Jr. into the O.F.C., continued by George Stagg and later Henry Naylor, followed by Albert Blanton, allowed the Crow torch to pass on fourscore years.

After Prohibition, Al Geiser ran the Ancient Age distillery with Elmer T. Lee as plant manager, using newly kit-out equipment for greater capacity. Much of the old plant had been stripped out or degraded under years of Prohibition dereliction. In early 1972, Gary Gayheart became head distiller. In May 2005, Harlen Wheatley replaced Gary Gayheart as master distiller, ensuring the distillery remains under his capable stewardship with Sazerac President and C.E.O. Mark Brown.

Buffalo Trace and Taylor bring another interposition to the coda. Edmund Taylor owned the two distilleries with the longest continuous whiskey production in North America: Woodford Reserve (Oscar Pepper) since circa 1831 and Buffalo Trace (Old Swigert) since 1858. Both distilleries continue to produce acclaimed whiskeys. Both distilleries continue to push, explore and test production and sensory boundaries to formulate and manufacture America’s topmost whiskey.

Old Taylor distillery, Glenn’s Creek: The Lever Food & Fuel Act of August 1917 stopped production from January 1918, shutting down the Old Taylor distillery for eighteen years. After Edmund Taylor Jr.’s death in February 1923, his sons Jacob, Kenner and Edmund W. Taylor held the trademark and property. They sold bonded stock to licensed medicinal bottlers before selling E. H. Taylor Jr., & Sons and the Old Taylor distillery to American Medicinal Spirits Company in July 1927. Otto and Richard Wathen’s American Medicinal Spirits Company was formed from the Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Company of 1920. In 1927, the National Distillers Product Company bought a 38% stake in American Medicinal Spirits Company, completing the buyout in December 1929 and entirely under National Distillers control in 1935.

The repeal of Prohibition saw the Old Taylor distillery refurbished and recommence production in May 1936 with 6,800 proof gallon-a-day capacity, triple the output under the Taylors’ management before Prohibition. By 1961, the distillery had been expanded and doubled production output to 1,000 barrels a day, selling 1,196,000 cases, becoming the fifth largest-selling straight bourbon whiskey. As the bourbon sales peaked in 1972, the distillery closed, with the warehouses continuing as a storage and bottling site until 1979. James B. Beam Distilling Company, part of American Brands since 1967, bought a portfolio of National Distillers whiskey brands in May 1987. The $545 million purchase tripled the size of Beam’s bourbon business with Old Taylor distillery and trademarks in the bundle. After stripping the plant for scrap metal, they sold the distillery in 1994 to Cecil Winthrop and Robert Simms of Stone Castle Properties for $400,000.

The distillery was again sold to Heart Pine Reserve who intended to dismantle the distillery and sell the limestone blocks, bricks and antique heart pine timber to the building trade; however, the 2009 G.C.F. and housing market collapse scuttled this plan. In May 2014, the decaying distillery was sold to investment group Peristyle for $1.5 million. Meanwhile, Beam Global Spirits and Wines sold the Old Taylor trademarks to Sazerac Inc. in June 2009. In 2018, the Old Taylor distillery reopened as Castle & Key distillery, owned by Will Arvin. The Old Taylor trademark owned by Sazerac Inc. and manufactured at the Buffalo Trace distillery continues at the site of Edmund Taylor Jr.’s O.F.C distillery.

Coming next week, Chapter 3 will investigate the first five decades of Taylor’s life. His involvement with the Oscar Pepper distillery and Johnson distillery, the new Hermitage distillery and new Old Crow distillery, until Taylor purchased the Old Swigert distillery, which became the O.F.C distillery.

*Honorable, the formal address given to Taylor as he served as the two-term Mayor of Frankfort Kentucky, later State Representative, State Senator, and an honorary Colonel, as civilian aide-de-camp to the Governor of Kentucky.