The growing popularity of whiskeys made with unusual grains—and non-grains—like oats, triticale, sorghum, and quinoa has got me wondering something: If you can distill alcohol from any grain, how did barley, corn, wheat and rye become the grains of choice for whiskey? And why are corn and rye mostly associated with American whiskey styles, while Scotch is associated with barley?

The general answer is that distillers have, historically, always worked with the grain available to them. In wet, chilly Scotland, where many grains don’t do well, barley thrives. It’s also easier to malt than other grains, and since malt contains diastase, an enzyme that turns starch into sugar, it’s easier to distill (which is also why malted barley typically shows up in bourbon and rye mash bills). Kentucky, meanwhile, is a prime corn-growing region, while rye grows best in cooler climates—which is why rye whiskey has historically been associated with the Northeast and Canada.

But how did these practical considerations eventually yield legal mandates about how whiskeys with different mash bills can be labeled?

Around the turn of the 20th century, whiskey labeling in the U.S. was virtually unregulated. In 1897, the bottled in bond designation was created by the appropriately-named Bottled-in-Bond Act; whiskeys with this label were guaranteed to be free of additives and aged at least two years. But it gave no specifications on what could be labeled “bourbon,” which meant anything from rye whiskey to blended or rectified juice could be sold as such.

Enter William Howard Taft—yeah, that William Howard Taft. In 1909, the president weighed in on the issue with the so-called Decision on Whiskey, which laid down a host of rules on what whiskey is and isn’t. Among those rules was the requirement that bourbon be made from at least 51% corn, and rye whiskey be made mostly from rye.

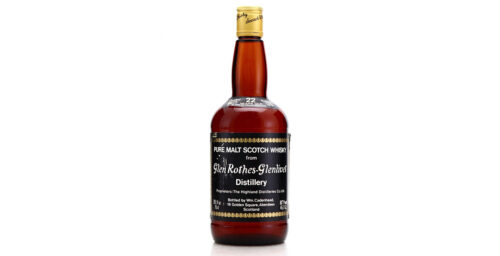

Our friends across the pond long took a more hands-off approach. The same year the Decision on Whiskey came out, a Royal Commission on Whisky ruled that Scotch whisky was distilled from grain mash, but took no stance on which grains could be used, saying,

“The Commission reports that it is not desirable to require declarations to be made as to the materials, processes of manufacture or preparation, or age of Scotch whisky, Irish whisky, or any spirits to which the term ‘whisky’ may be applied as a trade description. ‘The customer,’ the Commission adds, ‘asks for a glass of whisky and gets it. As a rule, he does not ask for any particular description of whisky. The customer knows what he likes, and if he does not get it he seeks for it elsewhere.'”

It wasn’t until a hundred years later that UK lawmakers opted to give drinkers more information. In 2009, the Scotch Whisky Regulations finally specified that malt, grain, and blended scotch whiskies had to be labelled accordingly.