Editor’s Note: Today we launch an ambitious nine part series chronicling the life of James Crow, an extremely important figure in the history of American whiskey. A chemist originally from Scotland, he is credited by some as having invented the sour mash process. Watch this time slot on Thursdays (11am Pacific Time) for the other articles.

Introduction To The Chronicles

One of the most significant contributors to America’s whiskey industry was the Scotsman, James Crow. Trade journals in the 19th century described Crow’s approach to making whiskey as ‘novel’; in other words, a new method. While he did not invent new processes, his disciplined and scientific approaches replaced the traditional and rustic methods, bestowing him recognition as one of America’s most influential whiskey distillers.

More than a decade after his death the Old Crow sour mash whiskey brand was trademarked, and successive distillers faithfully replicated mash whiskey to the same high-quality standards as Crow trained them. A century later it became America’s bestselling whiskey and the first bourbon whiskey brand to exceed sales of a million cases per annum.

The James Crow Chronicles investigate Crow’s life and examines the state of whiskey production and knowledge in Scotland and Kentucky in the 1820s (Parts 1 & 2). Transcripts and other primary archival sources provide enough records to reconstruct Crow’s production methods by the mid-1850s (Parts 3 & 4) and the conditions of whiskey distilling in Woodford County where the Oscar Pepper distillery was situated, where Crow did his work (Part 5).

While Crow and his acolytes were secretive about many aspects of the sour mash process, there is sufficient information to gain practical knowledge and insight into many of the details of his practice. More than a decade after his death, the Old Crow whiskey brand was conceived and so to, the construction of the Old Crow distillery a few miles down the creek from Oscar Pepper’s distillery where Crow did his work.

At the new distillery, his sour mash methods continued under distillers trained by Crow. They adjusted Crow’s methods as changing technologies, raw materials, and mass production efficiencies forced modifications and improvements to product quality (Parts 6 & 7).

After Prohibition, the saga becomes a story of corporate take-overs and further formula changes, leading to Old Crow becoming America’s best-selling bourbon (Parts 8 & 9). Crow never called his whiskey ‘bourbon’; it was always ‘hand-made sour mash whiskey’; the bourbon appellation first appeared on Old Crow labels two years before Prohibition. James Crow and Old Crow whiskey embody the story of America’s native spirit, and both played central roles in the frequently tumultuous first two hundred years of bourbon history.

The Education Of Crow

At the dawn of the bourbon industry, James Christopher Crow was as influential in American whiskey as he was enigmatic. Enigmatic, because he left no records. Even distillers trained in his methods also kept many parts of the Crow process veiled in secrecy – like the guilds of old, by stealth they communicated their masonic-like teachings to apprentice distillers, gaining wider dissemination and eventually broad adoption.

Crow did not invent the methods he was credited for; however, his scientific enquiry into product quality and production standards lay the formulaic foundations and empirical methodologies that profoundly influenced the development of the modern bourbon industry. Crow lived before the Civil War when Kentucky’s whiskey production was still a cottage industry consisting of thousands of ‘hand-made’ small farm distilleries.

After the Civil War, new capital and a regenerated America transformed whiskey distilling into one of the country’s major manufacturing industries. Other mid-western States like Ohio and Illinois later dominated whiskey production with 75% of whiskey volume; they lacked a commitment to manufacturing whiskey to a standard, not to a price.

His life may be shrouded in mystery; however, it is possible to decipher many of the technical contributions Crow brought to sour mash bourbon distilling. The first mystery starts with his date of birth. The absence of official accounts, Crow has two attributions to the place and date of his birth. Either June 11th, 1787 in Inverness, in northern Scotland to William and Katherine Crow; or 1789 at Dirlton East Lothian, south Scotland. He married Eliza circa 1811, and in 1812 their only daughter Catharine was born; both died a few years after his death and were buried beside Crow in Versailles Cemetery in Woodford County. James Crow died April 30th, 1856 at the Anderson Johnson distillery on Glenn’s Creek where the Crow family lived, and he distilled.

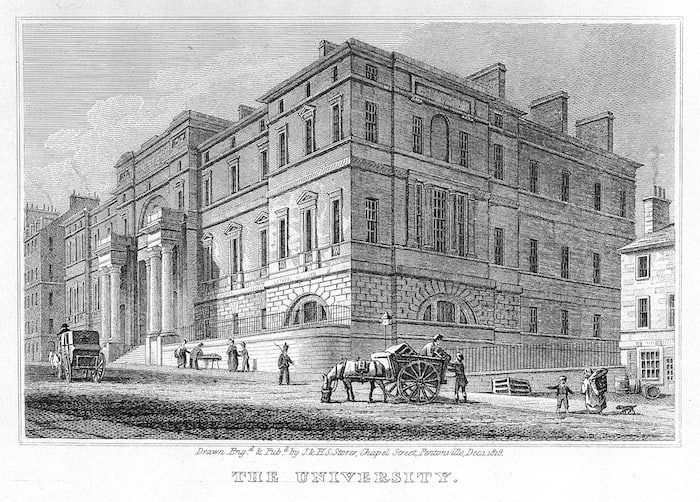

Whichever date he was born both have him studying at Edinburgh University in the early 1820s as a mature student in his early thirties; assuming the anecdotal records are correct and was not working as an assistant to a lecturer; which the University does not record. As the average life expectancy in Britain was 40 years of age, his return to studies and sufficient income to support a family indicates he had the means and ambition to improve his station in life. Decades after his death he was credited to be a graduate of Edinburgh University Medical School in 1822; however, there is no official record of Crow enrolled as a medical student, nor any Crow studying at the University between 1726 and 1866. The other faculties at Edinburgh University from 1587 to 1858 document, not a single Crow gained a diploma or graduated.

Decades after Crow’s death, a local newspaper started inaccurately adorning his name with the title, Doctor. In the 1950s, brand marketers of Old Crow whiskey recycled this misattribution in national magazine advertising; they also added the new tile, Colonel, to Crow’s salutation.

As Edinburgh University’s Science faculty was not established until 1893, it is more likely Crow undertook selected classes in natural sciences, that formed part of the medical course equipping him for his future employment in brewing and distilling. Edinburgh University’s Centre for Research Collection advised in 2020 many students in the 1820s could not afford the cost per class attendance and the expensive graduation fee, many left without a diploma, using lecturer endorsements and basic training to gain employment.

No images exist of Crow, only a vague description as thickset, with dark features and swarthy. Another mystery is why did an educated man remain a backwoods employee or distiller-for-hire, never owning a distillery, nor his own home. His private life as a roving distiller along Glenn’s Creek may always remain a mystery, not so his whiskey legacy. To understand how he applied his whiskey knowledge to bourbon production it is necessary to learn the level of practical distilling and scientific knowledge during the time he studied in Edinburgh and the state of the Scotch whisky industry by the 1820s.

Crow’s Academic And Literary World Of 1822

Edinburgh University’s Medical School was a four-year course obliging considerable wealth to pay individual lecturers over £30 per annum, plus matriculation fees, tutorials and living expenses. Many students at the time elected to pay the University ‘class tickets’, for courses they wish to study with particular professors, leaving when satisfactorily educated with references for employment. The tertiary education Crow gained in the sciences points to his vocational interests where the University was the world’s leading institution for instruction in brewing and distilling. His lecturers were eminent authorities in these branches of theory and application.

James Millar M. D, lectured on chemistry during the 1820s, publishing the erudite Elements of Chemistry in 1820. His subjects dealt with grains and malting practices, including the latest apparatuses and applications in fermentation and distillation. Newly published knowledge filled the library and local bookstore shelves with Andrew Ure’s 1821 edition of Dictionary of Chemistry, an updated work on brewing and distilling initially written by William Nicholson. Other scholarly books in circulation or reflecting current knowledge included Samuel Child’s seminal 1802 reprint Every Man his Own Brewer, and Samuel Morewood’s Inebriating Liquors and Distillation, published in London, 1824. From Elgin Scotland, an authoritative grain book on 1820s industry practices The Maltster, Distillers and Spirits Dealer’s Companion published 1828. Scotland by the early 19th century was the world’s scientific and industrial center for whisky distilling, with the University an academic fountainhead.

Scotland was also excelling as a world center in the manufacture of technical instruments and a leader in mechanical inventions, such as the steam engine, the driving force of the Industrial Revolution. Many of these inventions directly benefited the distilling industry, rendering distillers with better tools to measure, analyze and manufacture whiskey. The inventor of the saccharometer, Thomas Thompson, lectured at Edinburgh University in the early 1800s. His device measured the specific gravity in liquids, essential for brewers and distillers to monitor sugar to alcohol conversion during mashing and fermentation. The Scotch Board of Excise adopted the saccharometer in 1816.

Two years later the Government passed the 1818 Hydrometer Act gazetting the improved Bartholomew Sikes hydrometer for exclusive use by excise inspectors and distillers to measure alcoholic strengths at specific points during critical stages in the production process. It replaced John Clarke’s hydrometer, instituted since the 1787 Licensing Act, that superseded Dr Alexander Wilson’s hydrostatic beads invented in Scotland in 1757. US Congress adopted the John Dicas hydrometer in August 1790, when excise and customs duties needed gauging to help pay the Revolutionary War debt. The Dicas hydrometer was recommended by Governments until replaced by John Tralles hydrometer in July 1862.

Other Scottish inventions were reshaping manufacturing and entering distilleries, such as Boulton and Watt’s first rotative steam engine, installed at Stein’s Kennetpans distillery in 1787 to drive the millstones. Crow’s exposure to scientific disciplines, developments in distillation and the applications of new instrumentation in Scotland were destined to transform the manufacture of whiskey in Kentucky.

In part 2 next week we take a deep dive into the state of production knowledge, practices and equipment in Crow’s time.