Editor’s Note: We explore bourbon distiller Garrison Brothers out of Texas. Travel expenses were covered in part during our visit by the Texas Whiskey Festival, but editorial control of this article remains with The Whiskey Wash.

Dan Garrison of Garrison Brothers isn’t messing around when it comes to making Texas bourbon. His whiskeys are big, bold and sometimes brash, just like the state of Texas his distillery calls home.

To visit his ranch distillery, as I did recently on a trip to judge at the Texas Whiskey Festival, is to see first hand an operation that has emerged as one of the preeminent regional bourbon makers in the country. His is also one of the first distilleries in Texas in the modern era, giving Garrison Brothers a good number of years now to dial in on what makes solid Texas bourbon.

What can one expect to experience when visiting the distillery? A description posted on their website sums it up best by saying that “when you visit our Hill Country distillery, you feel a welcoming Texas spirit, right along with the aroma of sweet corn cooking up the sugary start to a tasty bourbon whiskey. You’ll ride an open-air, dust-covered bench-lined trailer, pulled behind a Jeep, from the planked, cabin gift shop and tasting room, up the wildflower-lined hill to the cookhouse and distillery. It’s a great way to get to know the soon-to-be-friends sitting next to you.

“As you wander the grounds with a masterful storyteller, you’ll smell the sweet Panhandle white corn cooking and taste the sugary sweet mash. You’ll taste the bitter distiller’s beer and tour the historic Stillhouse. You’ll sample the alarmingly high-proof white dog right from the stills and meander through the barrel barn to experience their latest limited release.”

And that’s a bit of the experience I got to have while there, plus the added benefit of some lengthy interview time with Garrison, which you can read below alongside accompanying photos and videos from my visit. Note that while this interview has been edited somewhat for clarity and brevity, I’ve left some parts more colorful in their language, if you will, to reflect aspects I feel best capture the nature of Garrison and his truly Texan operation.

The Whiskey Wash (TWW): How long have you guys been around?

Dan Garrison: We became a business or we were formed as a business by the Secretary of State’s office in Texas in 2006. We got our federal permit to distill alcohol in 2007 and got our state permit in 2007, as well. We knew we always wanted to make a straight bourbon so we didn’t sell our first bottles until 2010.

TWW: What’s your background prior to being a distillery owner?

Garrison: Helpless, lost, father of two, looking for what interested him. I really spent the first 35 years of my life wondering what the hell I was put on this planet to become and do. And I didn’t discover it until my first visit to Kentucky. In previous lives, I graduated from University of Texas in Austin in 1989, then moved to New York City, worked in New York City for about five years. Moved back to Texas because I met my bride in New York City and started working in advertising. Then jumped ship and went to a software company, worked there for about five years. And then I turned 40 and had a mid-life crisis, and decided to go start a bourbon distillery.

TWW: Why whiskey?

Garrison: I’ve loved bourbon whiskey since I was 13 years old. I think it’s the nectar of the gods. It’s the only alcoholic product that interests me. I’ve never been a beer drinker, never been a wine drinker. I love bourbon, I love the effects of bourbon. I like the health benefits of bourbon. I can say that because they exist. So everything about bourbon has always been all about myself as well. I love it.

TWW: So you started this distillery here in Hye, Texas. This has a bit of a ranch layout to it. Talk about your decision process on making this distillery like this versus something that’s maybe more in town or more urbanized.

Garrison: This area of the country I’ve loved since my wife and I had little kids. When they were three, four, five, six years old, they came out here, and we would do the Stonewall Peach Parade and Rodeo. It was always great to watch my kids do the mutton busting and all our friends and family kids doing the mutton busting at the rodeo. I’ve always loved this area of Texas, and I’ve always wanted to retire here. I ended up not retiring. I discovered that I wasn’t very good at retiring so instead I run a bourbon distillery.

TWW: You bottled your first bourbon when?

Garrison: January of 2010. Our first release was March 2nd, Texas Independence Day.

TWW: What was the Texas whiskey scene like in 2010?

Garrison: There wasn’t any whiskey in Texas. I think Chip Tate (Balcones) was the only other Texas whiskey distiller in 2010. I don’t know when Chip started. I think he started 2008 or 2009, but Chip was a little bit of a mad scientist, was using these real small barrels and putting them through all sorts of exhaustive heat treatments to make his whiskeys. With bourbon, it’s a totally different animal. That’s why he didn’t make bourbon in the early days. You couldn’t make bourbon that way because it takes three, four, five years in a barrel for the elements, the esters to come out of the woods. It’s got to sit for a while. And it sits and that oxygen flows in and out of the pores of the barrel, that causes esterification which is what homogenizes the molecules in the liquid. So when you drink it down, it’s not harsh anymore. Now it’s a soft, smooth, silky flavor. We didn’t want to release anything earlier than at least two years.

TWW: So what was it like trying to establish a whiskey distillery in this state?

Garrison: It wasn’t as hard as people make it out to be. Back then, everything was done manually. You have to get two permits. The federal permit, and then you have to get a state permit to distill alcohol. The federal permit was a monster. Terrible pain in the ass to get through because every time you would submit your application, and I did all mine by hand, there weren’t even attorneys qualified in the state of Texas to do that sort of thing because it had never been done before.

Texas regulations differ from the federal regulations significantly. I did all my own paperwork. I submitted my paperwork to the Tax and Trade Bureau at least 17 times. And every single time, they would send it back to me and say you missed item four on page 10. And I’d be like, “Oh, shit. What the hell is that?” And I’d go back to item four, page 10, and I’d reread the rules again, and I’d have to find someone at the TTB to talk to me. But they’re totally understaffed up there so they’re not receptive to questions. You have to keep trying and hope that you’re guessing correctly what was wrong with your original application. Finally got that permit in, I think, October of 2006, done in 2007.

Then once you get that, then you get to start phase two, which is the state paperwork. Take out an ad in the local newspaper, go talk to the county commissioners, let them know what you’re doing, go talk to the church leaders in your area. If you’ve got a lot of churches in your area, make sure that your property isn’t within a couple thousand yards of a school. You have to jump through a lot of different hoops to make sure they will approve your permit. In that particular case, I was able to go to the executive director, at the time, of the TABC (Texas Alcohol Control Board) and say, “Look, can you at least give me some help? Let me know who to talk to?” And he did. He was a huge help in getting this business underway. He gave me someone to talk to, and I was able to sit down with them across the table and say, “Okay, so I need to do this, this, this, and this, and then I’ll be approved?” Sure enough, they helped me.

I submitted the paperwork, and that process didn’t take nearly as long as I thought it was going to.

TWW: So you’re at this point making what is essentially Texas’ first bourbon. What was the initial feedback people were giving you about trying to make bourbon in Texas? Did they think it was a good idea? Did they think you were crazy? A little of both?

Garrison: The only opinions who mattered to me at the time were the Kentucky bourbon distillers. And they had to be senior enough in their organization to know the in and outs of it. Because if I had a penny for every single time that somebody said, “You can’t make bourbon from Texas. It’s all got to come from Kentucky,” I would be Tito’s today. But that didn’t happen. But you had to go to Kentucky to ask the right questions because that was where all the bourbon was aged. There weren’t any other bourbon distilleries in America so you had to go to Kentucky to get the right questions.

I remember sitting down with Dave Pickerell, and I had about four sheets of questions I wanted to ask him, and one of the questions I asked was, “What do you think the effect of year-round aging’s going to be?” 12 months out of the year, temperatures above 80 degrees. It could also be 20, 30 degrees in the morning. I said, “How do you think that aging environment is going to compare to what is happening here in Kentucky?” It was a pretty good question, I thought.

And Dave leans back in his chair and covers up his grizzly old beard, looks at me and goes, “I can’t wait to see it.” I could tell in his eyes, and the same thing with Elmer T. Lee, when I asked him the same question, at Buffalo Trace. He went, “Hmm, that could be very interesting.” Because they knew, they had tried, and they knew that the honey barrels, the good barrels at all of the rickhouses at Maker’s Mark and at Buffalo Trace were coming from the highest barrels in the barn. The ones all the way up on the top rick because they were closer to the sun. And the heat was rising internally within the building so those two combinations made it really, really hot at the top. They were losing more angel’s share from those ricks in the top of the building.

I thought to myself, if that’s the case, I can do low house rickhouses here. I don’t have to do high rickhouses like they do in Kentucky to get to the sun. I can do low rickhouses here because it’s going to be aging every single day, it’s going to get that heat. Just five barrels up, it’s going to be hot. And sure enough, it worked. We were right. I guessed right that it was going to cause more extraction from the barrels, and it was going to cause increased esterification of the sugar molecules. So it worked.

TWW: On your property you’ve got open warehouses. How do you find that this open environment plays with your barrels?

Garrison: We have three different pole barns that we’re filling as rapidly as we can, in fact, all of them are almost full. We have just contracted with one of my neighbors. We’re going to use an open-air turkey barn, which has got chicken wire all along the sides of the barn, so it’s going to breathe like a mother. This thing is huge. It’s 12,000 square feet. It’s long as a football field. We’ll be able to fill that with probably 9000 barrels in there. And that’s going to be the next new environment that we’re using. I think it’s going to have a very cool effect on the bourbon because it’s only going to go so high, it’s a very low building, but it’s really long so we’re going to get airflow through the building so every barrel in there is going to be hot as hell.

TWW: Let’s talk about the mash bill. What’s going on with it?

Garrison: The Small Batch bourbon is the same mash bill as the Single Barrel bourbon which is the same mash bill as the Cowboy bourbon which is the same mash bill as Balmorhea. We do have all sorts of experimental mash bills going on in the barns. Donnis Todd is our de facto crazy man. He’s got all sorts of wild ideas. He’s like the mad scientist of the place.

We’ve got bourbons aging with a high percentage of rye. I’ve got about 31 different recipes that are going on in the barns. The rye we’ll be trying next year for the first time. Rye is typically a much more dense grain so it takes a longer time for the sweetness to come out of the grain. We knew when we put those barrels in the barn it was going to take at least six years before we could release the rye. So the question is will there be any liquid left in those barrels, and we just don’t know. They’re hidden. Dennis has them hidden, and he’s going to bring them out when he thinks it’s time to bring them out.

We’ve also done some millet experiments with millet instead of wheat as the flavor grain. Rye experiments, we want to do a bottled in bond at some point. It’s not a different mash bill, but we’ve been doing it that way forever, we might as well release a bottled in bond so somebody has a collector’s item to live by.

We have Balmorhea coming out, which is a double-oaked bourbon. It’s still the same exact mash bill, but we’re doing different treatments with the wood. That’s what I like to do. I’m more interested in the wood. I believe that only 20, 25% of the flavor of good bourbon whiskey is coming from the grain and the water that you use. I think the rest of it’s all coming from the wood. I’m more interested in seeing what wood finishes will do to our bourbon than I am altering the mash bill or altering the white dog in any way, shape, or form.

TWW: Your bourbon mash bill is typically high wheat. Talk a little about why that, out of the gate, versus coming back with rye now and other grain types.

Garrison: It’s personal preference. I’ve been a wheated bourbon drinker forever. One of my favorites is Weller 12-year old. I grew up stealing my dad’s Weller 12-year old out of the liquor cabinet. That is basically a very similar recipe to Pappy Van Winkle, probably the exact same recipe to Pappy Van Winkle.

I like Maker’s Mark, for example. They’re sweeter, they’re a little bit mellower. I don’t like the spice that rye brings to a bourbon so I’ve never been a big fan of your Jim Beam’s or your Jack Daniel’s or your rye whiskeys.

TWW: You source your grains, the corn and the wheat, from Texas?

Garrison: We do. Originally, my neighbor who lived down the street from me in Austin, Texas was the procurement director for Whole Foods Market. Her name’s Betsy Foster. Good friend of mine. We drink whiskey together periodically. She’s a neat lady, and she buys all of the grain that Whole Foods buys. All the corn that they serve in all of their markets. It’s the whole ear of corn. I had never bought corn before, I didn’t know how to buy corn, so I said, “Hey, Betsy, I want to buy some of the highest quality corn in Texas. Where would you get that?” And she said, “Well, the Panhandle’s growing the most. The Gulf Coast area, also the Rio Grande Valley, also grows corn as well. But most of the good stuff is coming from the Panhandle because they’ve got unlimited water resources.”

A whole lot of them are doing it organically now, and I always knew I wanted organics. I wanted to be the first organic bourbon ever made. So she introduced me to Deaf Smith County Grain which is in Dalhart, Texas, and I literally loaded up my truck and drove up there, and asked the guy to throw in a couple of bags of their finest organic corn, yellow dent corn at the time. And they did, and I came back here. I tried it out, and it was converting 17 to 18% of the sugar to alcohol during fermentation.

Then I went back up there and got a second truck load. I came back and brought that down. Now the whole bed of my truck’s full of this stuff. I get down here, and I open up the first bag, and it says, “White corn.” Well, I didn’t want white corn. I wanted yellow dent because that’s what all the Kentucky growers had told me to use. I said, “Can I return this stuff,” and I realized to drive back to the Panhandle, take it all back, and do it would cost more than actually just trying it. We tried it, and my first yield of my first batch yielded 22% sugar, and I was like, “Shit. Maybe nobody’s doing white corn. Maybe that’s something that I should consider and, sure enough, I was getting so much more alcohol off of it, and I liked the flavor of the alcohol, the white dog, better than I did the yellow dent, so we switched to white corn.

TWW: You’re also making use of a red winter wheat.

Garrison: Yes, and we’re sourcing different suppliers for the wheat right now. I have 65 acres planted across the way, we’ve been farming that with organic soft red winter wheat. We’ve been doing that since 2005, but, honestly, the challenges of being a farmer and all the equipment that’s required, on top of running a distillery, it was just wearing me out. We were spending so much money on contract labor to come in and farm that field for us that it just wasn’t worthwhile.

TWW: You guys have a limestone aquifer here on the grounds. What’s your thought process on how that plays into what you guys craft as a bourbon?

Garrison: I’ve been on all these Kentucky tours, and I wanted to know everything that they told me. And some of the tour guides would say, “The reason that Kentucky bourbon is so darned good is because we sit on a limestone, it’s limestone filtered water which takes all the irons out of the water.” I already knew that if you had iron induced into your water stream, that it would take the white dog and it would turn black which is bizarre, but it does. It has some sort of chemical reaction. So you can’t have high iron water.

We have more limestone than they’ve got in Kentucky, for sure. The whole Balcones Fault Line that runs through central Texas from Waco all the way through San Antonio to south Texas is all limestone. And it’s dense limestone. The water quality, if you look at it, in this area is about 2500 parts per million of salty calciums, total dissolved solids. All sorts of calciums and sulfides and sulfites. That’s all the good stuff that cleans out that water, but it’s also food. It’s nutrients, it’s minerals. So during the fermentation process, the yeast has something to eat. So the yeasts get very excited. Nobody in Kentucky is going to get a 22% sugar result out of their fermentation, and that’s what we’re getting because all those minerals in that water that comes from the limestone aquifer is in the water. And so the yeast loves it. It’s food.

TWW: You guys collect rain water to proof down the whiskey with, yes?

Garrison: Correct. I think we’re about 200,000 total gallons [of rainwater catching capacity]. This area of the state only gets about 28 inches of rainfall a year. It’s very dry. We don’t get enough rainfall to protect the aquifers below us. At the time that I started the distillery we were in these major droughts and all of the major lakes in the area were drying up, and people were drilling holes in Blanco County for their own water wells, and they weren’t hitting anything. There was no water to be had.

So, all of a sudden, water became a big business in Texas and at the state capitol, everybody was very nervous about it. Since then, everybody’s been spoiled rotten because we’ve had a lot of rains. People aren’t taking it seriously anymore. But it’s a big deal. And I met this guy that ran this rain water company out of Dripping Springs, and he had all these tanks. It’s called Tank Town. He showed me the process and how it works. I sat down and I did all the math that he recommended to me to determine how much roof area capture space we had to have. I realized, wow, I’m going to be building all these barns so if I put rainwater collection on all of these barns, I could have a shit ton of water to use for proofing and for running my toilets and my faucets and cleaning, even for irrigation if I needed it.

So we tried to overbuild the roof line on all these buildings. That’s intentional to capture as much rainwater as we could off that roof line. We’re going to need water. Water’s critically important to running the stills, to running the cookers. You’ve got to have water so we use rainwater for that as opposed to the ground water. We only use the ground water from the aquifer for the cooking process.

TWW: Looking just briefly at your whiskey line, you’ve got your flagship bourbon, which is the popular one that’s proofed down slightly and sold in 26 states and six countries. You’ve got some of these smaller batch expressions. You’ve got Cowboy bourbon, and you’ve got the Single Barrel. Which is your favorite child among all of them? Or does it depend on the situation?

Garrison: The four fastest horses in our stable are the Small Batch, the Single Barrel, the Cowboy, and the Balmorhea. Those are the only things that we’re selling nationwide. All the other experimentals, we’re just trying here in Texas. Texas is our playground to determine what has viability for the future. Estacado and Honey Dew are two that we really can’t figure out how to commercially release, to produce enough of to have a commercial release nationwide.

But we do have something coming out in 2020 that will be very exciting. I can’t talk about it yet. We don’t even have a name for it. It’s just called Operation Cadillac. It’s ready to go, we’ve just got to get a name, we’ve got to get bottles, we’ve got to get labels, we’ve got to get everything painted and printed. We’ve got to get pricing structures into the distributors.

TWW: It’s often a standing thing among some bourbon distilleries to have most of your product proofed down, but then have that one, big, punch you in the face bourbon, and that’s your Cowboy bourbon. Talk a little bit about your thought process behind that.

Garrison: We’re still small enough, and we intend to stay small enough that Donnis and I can go into the barn and we can taste barrels to see what we like and what we don’t like. We taste every barrel at four years of age. And when we find a Cowboy barrel, it’s going to be sweet, it’s going to be crème de la crème of all the barrels that we’re tasting that particular year. So we set those barrels aside. We’ve got a secret location for them. This secret location is called the honey spot for where the barrels are located on the ranch, and nobody gets to know about it except for Donnis. I don’t even know where these barrels are hidden. But I know it’s there, and I know he’s got something up his sleeve because they always come up consistently beautiful. That Cowboy bourbon is uncut, it’s unfiltered, and it’s right out of the barrel. We’ve done four releases of Cowboy bourbon, and they have ranged from 135 proof to 142.5 proof. And it sounds like it would be a dizzyingly painful thing to drink, but it drinks like Kool-Aid. It’s very smooth.

TWW: With your Single Barrel program, talk a little bit about that and what you guys have going on around that.

Garrison: You can buy our Single Barrel bourbon three different ways. You can buy it by six-pack samplers. If you are more interested in something you could personalize, then you can come out here, pick a barrel, and we’ll bring a whole bunch of friends out with you, and we’re going to give you drills, and you can go up to each barrel, take a little sample off of it, and when you find one you like, we’re going to staple a tag on it that says your name and when you selected it, and then we’re going to cook you fried chicken in our barrel barn, in our little catering kitchen over there, and you and all your friends can have lunch. And then we’re going to come back and we’re going to proof that bourbon down to 94 proof, and we’ll bottle that bourbon. We’ll let you do the bottling. It’s actually a great time. People bring groups of 20 out all the time to do it.

If you want to, you can also choose to have that barrel proofed so it’s like your own personal Cowboy bourbon. What always astounds people that come do a barrel selection is the range. One barrel from a cooper that was aged just as long as the one next to it can taste totally different, and you never know what you’re going to get. It’s always a surprise, and it’s always kind of a fun project to do.

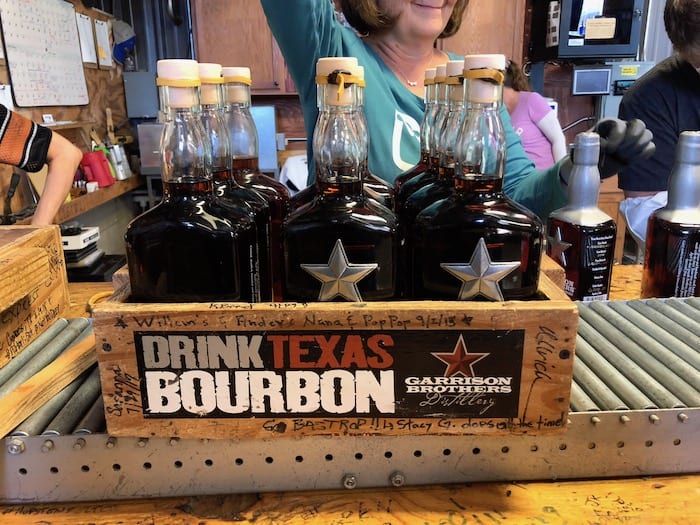

TWW: Speaking of people and having fun here, a big component of what you guys do is a bottling volunteer list. Can you talk a little bit about that for a moment?

Garrison: Today [the day this interview was done] we have 24 people here from all walks of life. We have lawyers, we have truckers, we have cab drivers, dancers, strippers, restaurateurs, all on the bottling line, and they all are getting along so fine because good bourbon makes friendships. It creates legendary friendships that can last a lifetime. At 9:00 in the morning, we get started, and by noon these people are exchanging their phone numbers and their email addresses with each other so that they can come back and do it next time.

We have 17,000 people on the waiting list to come bottle for us at this date. But it’s not as difficult as it sounds to get in because if we need 500 volunteers to bottle from March through June, we’ll send out to 1000 people those 500 slots so you got a two in one chance of getting it. And those names that we select from the 17,000 person list are randomly selected. It could be somebody that signed up yesterday or somebody that signed up 10 years ago. Everybody has an equal shot to get in.

TWW: Where do you want to see Garrison be in a year, five years, 10 years?

Garrison: As I mentioned earlier, bourbon is all I drink so if I travel to another country, and I can’t get Garrison Brothers there, it breaks my heart, and it makes for a miserable vacation for my wife because I’ll bitch the whole damn time we’re there. So I would like to see Garrison Brothers in every country in the world. That’s my lifelong dream. I want to hang on as president and CEO as long as I can, I want to see that happen in my lifetime, and I won’t retire until I see that it’s going to happen.