For those of you having gone through or still undergoing the tax-preparation process, our sympathy. For those of you having to read IRS documents in the original, pour yourself a double. Understanding these pains, what would provoke a rational man like Todd Leopold, head distiller of Leopold Bros. distillery, to study IRS documents of the 19th century?

Easy: curiosity. Specifically, curiosity about the rye distilling practices of that time, which indicated some unusual equipment and techniques—three-chambered stills being foremost among them. “I’m just curious,” says Leopold. “There really aren’t any modern books that are particularly helpful when it comes to the practicality of running a still.”

Leopold didn’t merely read the IRS studies on whiskey production practices; he read broadly across technical distilling documents from the Pennsylvania and Maryland distillers of those days. “That’s what led to me stumbling across the first mention of the three-chamber still,” he says. What he discovered was that emerging modern distilling practices abandoned the more flavorful—but more demanding—whiskey output of the chambered stills for the efficiency of column stills.

Spirits experts like David Wondrich and Chuck Cowdery had written of the virtues of three-chamber stills and published old illustrations, which Leopold too saw in his research. “These weren’t plans or engineering drawings, but illustrations,” Leopold says. “They didn’t provide the pertinent engineering and pipework, and that kind of stuff.”

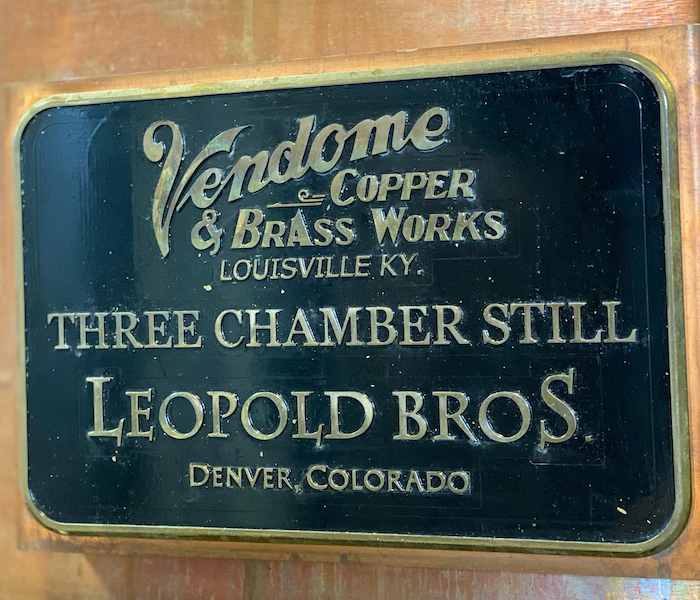

That kind of stuff was provided by Vendome, the Louisville-based metal fabricator that has made its innovative way around stills for well over 100 years. “Where Vendome helped me, which was way above my pay grade, was the metallurgy,” says Leopold. “In other words, where were the stress points? It’s not like a column: it’s 20 feet tall and four feet in diameter, and you’ve got mash sitting in four separate chambers. One of the chambers is 15 feet off the ground and you’re bubbling through it,” he says.

Since he’d never made one before, Vendome’s president Thomas Sherman told Leopold he couldn’t guarantee it was going to work, but Leopold gave the go-ahead. “I understood how the still worked before we installed it, and that was the key behind it. That made it so my brother was dumb enough to cut a check for it,” says Leopold. “It’s a very stout still—Vendome has been making stills for an awfully long time.”

Chamber Music

When Vendome’s Sherman said that Leopold was “taking things in an interesting direction,” he meant it. “You have to understand that each one of the chambers is its own little animal,” says Leopold. “The temperature is different in each chamber and during the operation, there are chambers that are under pressure that you think are under vacuum, and the chambers that are under vacuum are the ones you think are under pressure. It was counter-intuitive to get everything running and moving from charge to charge correctly.”

One of the significant differences in how a chamber still works as opposed to a column still is time. From entry to exit for mash in a column might be a mere 90 seconds. The movement of the mash through three active chambers via steam heat is more leisurely: a run can take 90 minutes. Because temperatures and pressures are higher, good whiskey things happen: “Because you’re basically bubbling that live steam through water, the pressure goes up, the temperature goes up and you’re extracting things that are soluble in water,” says Leopold. “That temperature being higher has a tendency to pull out compounds that are more water-soluble and that means oil.”

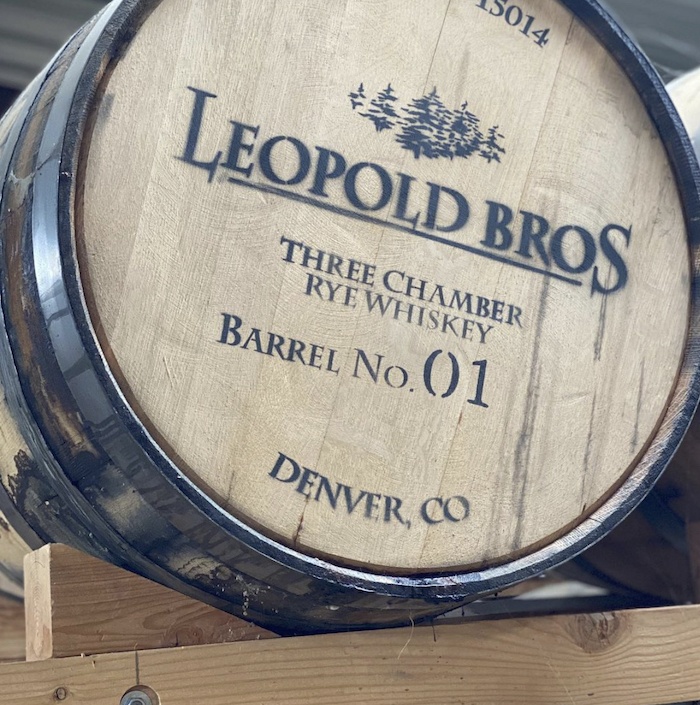

When Leopold calls the chamber still an “oil-extraction machine,” he means it produces unique concentrations of congeners and other flavorful spirits constituents. He brings his rye out around 100 proof and into the barrel at 100 proof, which is all of a piece with the whiskey characteristics he is looking for. “I’m not interested in the tannins and some of the heavier compounds that you get out of the wood, which extract out much faster at higher proof,” he says. “Going in lower instantaneously makes it a softer whiskey. The barrel isn’t as dominant. That was straight up the way that American whiskey producers were doing it in the 1800s.”

Among the company’s eight stills are a vodka column that is attached to a pot still, a couple of German CARL stills, and a couple of other Vendome stills. “We have a few alembic stills that we make our Maryland rye and our bourbon in,” says Leopold. “And then we have one more alembic for the vodka, and then a pot and column assembly for the second distillation to make that a 95%-plus spirit. And then obviously the three-chamber still. We have a different tool in the drawer for whatever it is we’re trying to do.”

Leopold disagrees with the production of cask-strength whiskeys that are then watered for a certain bottle proof. “You’re washing out all the flavors, you’re washing out all the oils that have been extracted and the compounds out of that barrel and diluting the flavor, diluting the mouthfeel, diluting the color, a little bit of everything,” he says.

The company’s dunnage-style warehouse, with its dirt floors and its moderate temperatures in the dry Colorado air, also holds the entry proof in the barrels. “One of the neat things about our warehouse is that the proof doesn’t move, which is a quirk of our warehouse and not something that we had planned,” he says. “So we’re in at 50% and we’re out at 50%.”

Grains and Malt and Fruit

Another thing those early whiskey producers were doing was using grains, notably rye, that had a much lower starch content than the grains of today. The distillery has a partnership with a local farm growing Abruzzi rye, an heirloom grain with significantly lower starch content than most commercial ryes. Leopold Bros. avoids adding artificial enzymes during fermentation because they aren’t looking for maximum yield—they are looking for flavor.

A big kick of that flavor comes from their own malted barley, produced right at the distillery. “If you take the Abruzzi rye and you mash naturally versus adding these enzymes, when you add the enzymes, you’re going to wind up getting more fermentable sugars, therefore more alcohol,” says Leopold. “But you’re doing that at the expense of diluting the aromas and flavors that you’re getting out of the grain.”

Their malting program has been such a success that the distillery sells their various malts through Brewer Supply Group, the largest wholesaler in America. Leopold’s 15-year history with beer brewing gave him a unique and educated perspective on malts, which has influenced much of the whiskey production. They use their malts in their bourbon and an unreleased malt whiskey, as well as their vodka.

Among the whiskeys that Leopold Bros. makes are several that are blended with fruit and aged in the used bourbon barrels. “So the whiskey is maturing, and we’re lapping up some of the flavor from the previous contents, bourbon obviously,” he says. “There are multiple things that are happening in the barrel: the whiskey is maturing, but also fruit is oxidizing. You have flavors that are similar to a port or a sherry where you’re oxidizing that grape juice.”

Flavored whiskey can get a skank eye from purists, but Leopold won’t have it. “The people that are very serious about whiskey don’t necessarily understand—they think flavored whiskey is some horrible thing, and they’re forgetting that was a very common way of drinking it,” he says.

“This is something that was traditionally made to make the spirits coming off of a family still more palatable. It’s just elevated a little bit in that I’m putting it in the used cooperage and trying to get a little bit more finesse into the whiskey. We’re not trying to go to the lowest common denominator; we’re trying to make something that’s unique and different.”

The distillery also produces a couple of gins, a Fernet, an Absinthe, an Aperitivo and several liqueurs. They have been holding on to their Maryland Rye in order to release a five-year-old bottled-in-bond version. But the real excitement is that they are on the verge of releasing the first bottling from the three-chamber still, which will be named, appropriately enough, Leopold Bros. Three-Chamber Rye Whiskey.

“The whiskey we will release is going to be labeled as bottled in bond,” Leopold says. “We’re dealing with the same thing everybody else is right now, and that’s COVID delays for everything. Doesn’t matter what it is—packaging, bottles, labels, you name it. Everything’s kind of slow going. But we’re about a month out and we’re pretty excited.”

The folks at Leopold can probably handle the wait. Since Todd Leopold’s first diggings into 19th-century whiskey heritage, time (in and out of the barrel) has been on his side.